No 3: Video und Überwachung

No 3: Video und Überwachung

[english version below]

Welches sind die tieferen kulturellen Veränderungen, die sich aus der Verbindung von Video und Überwachung ergeben? Grammatik der Überwachung umfaßt drei grundlegende Texte, die das Feld der Anwendungen mit seinen unterschiedlichen Bereichen beleuchten. Thomas Y. Levin skizziert den Stand der technischen Möglichkeiten der Überwachung und seine Wechselwirkung mit den Darstellungen und Kontrollphantasien, die in den Massenmedien geprägt werden. Sein Fazit ist, daß der überwachende Blick seine abschreckende Wirkung verloren hat und zu einer 'Technologie des Selbst' umgedeutet wurde. Winfried Pauleit beschreibt die Videoüberwachung als eine Bildmaschine im Futur II: als Photographesomenon. Die Logik dieser Bildmaschine hat weitreichende Konsequenzen für die Konstitution zeitgenössischer Subjekte, wie auch für die Felder der Ästhetik und Wissenschaft. Thomas Weaver dekliniert die Struktur panoptischer Überwachung am Fall James Bulger. Er zeigt die genealogische Linie auf vom Panopticon zur heutigen videoüberwachten Shopping Mall und benennt dabei die Konsequenzen als Scheitern des Sicherheitskonzepts und als Theatralisierung des Verbrechens.

Dispositive der Überwachung fragt nach den Anordnungen medialer Kontrolle in Fernsehen, Fotografie, bildender Kunst, Film und Internet. In Analogie zu den zwei Körpern des Königs (Kantorowicz) beschreibt Ralf Adelmann einen dritten Körper als 'body video' im Kontext Fernsehen. Als Beispiele dienen ihm die Ausstrahlung von Videobändern dreier Politiker: Hans Martin Schleyer, Bill Clinton und Joschka Fischer. Heather Cameron beschreibt aktuelle Kamera- und Satellitentechniken als Weiterentwicklung eines fotografischen Dispositivs. Sie kontrastiert ihre These mit den Strategien der Fotokünstler Steve Mann, Sophie Calle und Christian Boltanski. Christa Blümlinger skizziert modellhaft an einer Arbeit des Filmemachers Harun Farocki das zentrale Dispositiv von Videoinstallationen als Überwachungsanordnung. Marc Ries dagegen erläutert eine grundlegende Kontrollfunktion des Kinos an einem Film von Francis Ford Coppola. Eine Bannung des Überwachungswahns wird von ihm im sozialen Aspekt von Film und Kino in Aussicht gestellt. Eva Reinegger stellt schließlich Überlegungen zu den Dispositiven Webcam und Girl-Cam an.

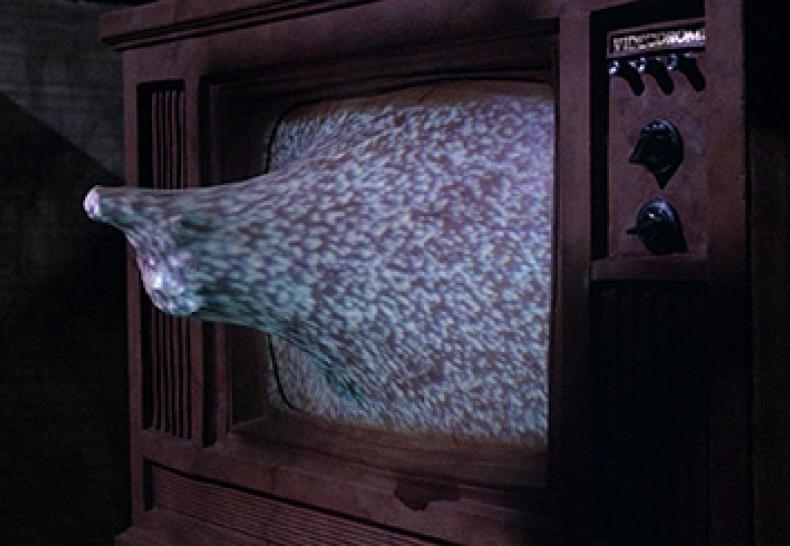

Subjektgeschichten versammelt reale und fiktive Fallbeschreibungen, die die Subjektkonstitution unter dem Kameraauge thematisieren. Christina von Braun schlägt einen Bogen von der Audiovisualität des Mittelalters (Artuslegende) bis in die Gegenwart (einem Fall aus der psychoanalytischen Praxis) und zeigt, wie sich die aktuelle Definiton von Geschlecht mit dem einseitigen Blick der technischen Sehgeräte verbindet. Eine mögliche Rückkehr zum Dialog deutet sich schließlich mit Jane Campions Film The Piano an. Sabine Nessel unterstreicht die Bedeutung des Videobandes in der Fallgeschichte Lortie (nach Pierre Legendre). Die Ausstrahlung der Videoaufzeichnung im Gerichtssaal initiiert eine Übertragungssituation, die derjenigen in der Psychoanalyse vergleichbar ist. Michaela Ott untersucht den Gebrauch von Videobildern im Film. Anhand von Cronenbergs Videodrom, Atom Egoyans Family Viewing und David Lynchs Lost Highway lotet sie sowohl die Ausweitung der Kontrollfunktionen der Videotechnologie als auch die Möglichkeiten zum subversiven Gebrauch aus. Jörg Metelmann entwickelt schließlich aus einer Filmerzählung Michael Hanekes einen kategorischen Video-Imperativ, der sich zu einem System jenseits humanistischer Kontrolle verdichtet.

Die No 3 begleitet mit 'Video und Überwachung' die Ausstellung des ZKM Karlsruhe: CTRL [SPACE]. Rhetorik der Überwachung von Bentham bis Big Brother, 13. Okt. 2001 - 24. Feb. 2002

Für die Redaktion Winfried Pauleit

No 3: Video and Surveillance

Editorial

What are the deeper cultural transformations produced by the linkage between video and surveillance? The Grammar of Surveillance includes three fundamental texts, which illuminate the area of surveillance applications in various ways. Thomas Y. Levin sketches the state of the technological possibilities of surveillance and its dynamic relation to the representations and fantasies of control produced by the mass media. He concludes that the gaze of surveillance has lost its frightening effect and has become a "technology of the self." Winfried Pauleit describes video surveillance as an image machine working via a time loop in a future perfect: as Photographesomenon. The logic of this image machine has far-reaching consequences for the constitution of contemporary subjects, as well as for the fields of aesthetics and academic knowledge. Thomas Weaver declinates the structure of panoptic surveillance by looking at the case of James Bulger. He shows the genealogical line from the panopticon to the video surveillance of the current shopping mall. In so doing, he sees the failure of the concept of security and the theatralization of crime as the consequences of this development.

Apparatuses of Surveillance interrogates structures of media control in television, photography, the fine arts, film and the Internet. In analogy to Kantorowicz's notion of the king's two bodies, Ralf Adelmann describes a third body as "body video" in the context of television. As examples he uses the effects of the video tapes of three politicians: Hans Martin Schleyer, Bill Clinton and Joschka Fischer. Heather Cameron describes certain camera and satellite techniques as a further development of a photographic apparatus. She contrasts her thesis with the strategies of the photo artists Steve Mann, Sophie Calle and Christian Boltanski. Using the example of the film maker Harun Farocki, Christa Blümlinger sketches out the central apparatus of video installations as an order of surveillance. Marc Ries, however, explains a basic control function of the cinema by looking at a film by Francis Ford Coppola. He proposes that the social aspect of film and cinema might offer the possibility of an end to the surveillance craze. Finally, Eva Reinegger presents her thoughts on the apparatus of the webcam and Girl-Cam.

Subject Histories is comprised of real and fictional case studies which thematize the subject construction under the eye of the camera. Christina von Braun traces a line from the audiovisuality of the Middle Ages (the legend of Arthur) to the present (a case from psychoanalytic practice) and shows, how the current definition of gender is linked to the one-sided gaze of technical devices of vision. A possible return to dialogue is shown with Jane Campion's film The Piano. Sabine Nessel underlines the significance of the video tape in the case history of Lortie (after Pierre Legendre). The showing of the video tape in the court room initiates a situation of transference, comparable to that in psychoanalysis. Michaela Ott looks at the use of video images in film. Using Cronenberg's Videodrom, Atom Egyoan's Family Viewing, and David Lynch's Lost Highway, she addresses both the extent of the control functions of video technology as well as possibilities for their subversive use. Finally, Jörg Melemann develops from a film narrative by Michael Haneke a categoric video-imperative which consolidates to form a system beyond humanistic control.

'Video and Surveillance' accompanies an exhibit at the ZKM Karlsruhe: CTRL [SPACE]. Rhetorics of Surveillance from Bentham to Big Brother, Oct. 13, 2001-Feb. 24, 2002.

For the editors Winfried Pauleit

(Translation Brian Currid)