Surface Depth

Surface Depth

'Turbulent 1998', a film installation of Shirin Neshat at the Serpentine Gallery

... on vacation by the sea, not paying attention to anything much but the horizon and the unpredictable weather ... mid August and there is a familiar summer calm in the media ... though I hardly glimpse the papers or the TV news, I am aware of a strange and compelling parallel unfolding between two news events - is there anybody alive on board the Russian submarine, and who was going to be thrown out next in the TV show Big Brother. I did not seek out coverage, but I knew that the submerged horror of the KURSK submarine was seeping into the news blankly, without pictures, with dread and then suspended dread as the pulse of its images. In contrast, Big Brother was everywhere - imaged continually on the web and transmitted nightly on TV. Everything was visible, and yet even this was not quite enough; the hunger rages, and the appetite grows for the awaited public execution. These people are cut off from the world and cannot escape the confines of their cramped camp. They have to stick to a routine and carry out tasks to stop sensory deprivation. Trapped and on display, they are being watched 24 hours a day and have to abide by an exact set of rules. If they misbehave they will be thrown off. We are waiting to see one of them ousted by the group and by popular vote, we are waiting to see them suffer this rejection in front of us. But then we find out that all of them have died. The tight opposition between the space of dreadful imagining and the theatre of cruelty seems so glaring as to make it utterly implausible and painful. It seems as though the participants on Big Brother, (and the audience,) have consumed the dividing line between media production and lived life, the spectacle has been internalised, the production of TV is the same as getting dressed. Meanwhile from the cold depths of the Arctic Sea, images are not flowing to us, instead they swirl to make a black hole, a latent image of something that is there but which we cannot see. The two stories taken together register so loudly as East meets West, or rich and bored meets wounded and dangerous; some face to face encounter that seems so meaningful even though it is simply a media coincidence; an unintentional montage.

Shot - Reverse Shot

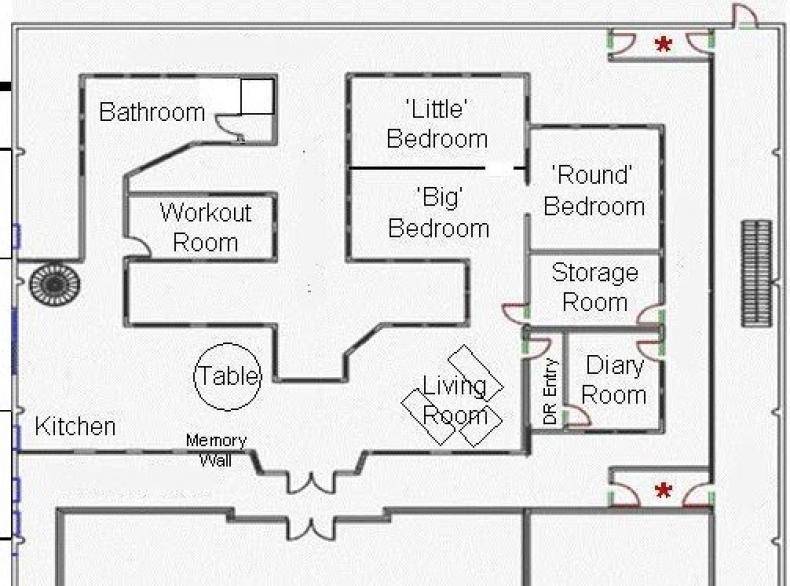

It seems to be an idle reflection, a kind of disengaged absorption of media information that can produce from these different stories a new and engaging pattern. I am prompted to hold onto this new cast after image in relation to the work of Shirin Neshat, Iranian/American artist, whose film installations have been here at the Serpentine Gallery in London for the month of August. It is perhaps misleading to introduce her work via the media stories I mention above as generically her work refers us to classic black and white cinema, and the whole quality of the productions speak not of immediacy but rather of extensive planning, collaboration and investment known only to the film industry. While her image sequences are clearly cinematic, the way she installs them - on split screens is not like cinema at all. This in itself is nothing new - many artists have turned to film and video, especially over the last decade, and many have experimented with multi screen works.

Neshat describes her work as a visual discourse on the subject of feminism and Islam. Her work demonstrates high film craft made with the assistance of a talented crew and a large cast. The images are clear, the performances resolved and the camera work precise. Neshat’s projects are funded and critiqued by the international art world. There is something of an east-west collision experienced when looking at her work, not simply because of its cultural displacement and its western financiers and audience, its subject matter of religious Islamic laws patrolling the activity of women, and its presentation in the liberal space of the art gallery, but also because formally Neshat works to produce and discipline image sequences of stark difference and high contrast, that are in some ways congruous with their cultural origins. That is her work does not immediately oppose Islamic conventions. In some ways her work seems very traditional - and that is definitely part of its mischievous appeal.

Turbulent 1998,

is the earliest and most formally resolved of the works on show. Two three meter projection screens mirror each other across the darkened gallery and the events unfold across the space, first on one screen and then on the other, held together by a single sound track. A man sings in Persian a beautiful melody, full of longing and love. He faces out from an auditorium and behind him is an audience of men. They all wear similar clothes, a simple white shirt and black trousers. When the song is finished the man rests his head in repose until he hears the stirring of a woman’s voice, he looks up, he looks out of the screen, across the gallery to the opposite screen where a veiled woman has been standing turned away, with her back towards us. She too is in an auditorium, the same place mirrored back, but it is empty except for her microphone and the curving steel tracks for the camera to follow. She begins to sing, strange sounds, no words, just sounds, bodily moans - wailings, crescendos and falls. The men look on, curious, arrested. Men watch, women appear. She chants and breaths and emits, the sound comes and comes again. The sound is engulfing and wrenching. The camera begins to move around her loosing the emptiness of the room and filling it with her large veiled presence and an intimate connection of body and voice and technology. She finishes and the music ends, the credits roll, there is a momentary freeze frame and then the man begins his tuneful lament and we start over.

The two screens facing each other create a distinct illusion of coherent time and space. The situation is impossible, as both sequences are clearly shot in the same place, but are played together as if forming a shot reverse shot. The figures respond to what has taken place in their own space, and in the one opposite them, a separate but visible reality. The separate screens seem to be conscious, they have come alive, and engage like chess playing itself. While one end is active the other waits. The whole held tightly together by the timing of the sequential actions, the watchful presence of the men and the coherence and continuity of the sound track. The whole is taught, like classic realist drama, yet the space in between - through which the communication takes place is the middle of the gallery. As the action moves from one screen to the other, so the space normally taken by the gallery viewer becomes a kind of territory, a no-mans land which is very uncomfortable to traverse. The middle of the gallery, the prime space for looking at art, is occupied. The viewer, cannot but rest on the edge, displaced from the conventional seat facing the screen. Our view will be just outside the recommended optic of the projector. It does not mean we cannot see, it does not produce incoherence or fragmentation, not at all - we can see the work from the edge even though we will always have to miss something as we turn to watch one screen or the other. What we witness from the edge is film engaged in a passionate and curious dialogue with itself. It is beautiful because it reveals what cinema hides - the way the spectator is normally enveloped by the apparatus. The shot reverse shot - a marvellous illusion in the montage of cinematic space giving the viewer almost unlimited fluidity of mind and body - is set up here to be self sufficient , an almost private event. We are not ‘in’ the seduction, we are kept out. It’s like a model revolution, the screen images have liberated the means of production, leaving the owner/consumers out of the picture. Perhaps one effect of such a work of exclusion could be for a desire to go back to something we once had, but is here missing - our sovereign seat, our place in front of the screen.

As you stay with this installation you being to notice its seams and to question its making. If you stare at the lovely man singing, you will notice he is not singing, but lip synching into a large retro radiator microphone. There is a certain nostalgia to this formation - it refers us to the distinct technologies of sound and image which is, in itself, a rich vein of film history. The film we are watching was made two years ago, but it somehow produces a current of loss that is about the past, a longing for the past, a thematic held in an industrial order or relations - of cinematic hey day and big machines, modern times. They say you can gauge a social order by its technological mode - so can you read the references to technology as a particular state of longing? If so, the man who lip synchs out at us speaks of a utopian industrial age.

Look again at the woman as she wails her sounds and you will see that here too there is no exact match between her singing and the sound, yet the effect is quite different, she isn’t miming to a recording of the sound, but neither is she the immediate producer of all of it. The sound comes from her, it sounds like her, but it is more, repeated altered. The technology of sound is made apparent here - the gap between representation and referent is smudged, and the fuse of voice and not voice-sound becomes the song. This technological production is familiar territory of the avant garde. The performer here is Sussan Deyhim, composer and collaborator with Neshat. Deyhim is known for her experimental music influenced by Islamic mysticism and musical form. Her music is ancient and modern, it seems to have by passed the machine age and has emerged as digital. The man sings a recognisable song but he is miming, the woman produces the unfamiliar.

Aesthetic Law

Within strict Islamic law, women are forbidden to sing or perform in public. Here Deyhim is alone in the public auditorium. The men are watching her, but they are an illusion, a filmic animation. We are watching her, but this she cannot know. Is she performing in public? The scenario spells acts of transgression, and yet the actual flouting of laws is only hinted at. Her noise is unprecedented and non verbal, as if social conventions are absent and present at once, as if she has been prevented from articulating a clear social stand and has taken the stage to say the unsayable. Are we at a moment before proscription, or have we gone beyond? Is this cause and effect or some kind of futurism? She is being watched by an alarmed and captivated audience of men. The law is summoned up by the exchange between screens. It’s like a seance, we have called on the law. And oddly, the law here appears as part of the restrained beauty of the work. The work is coded, the formal restraint bears down on the binary male/female. The law is like an interiorised magnet in the imagination, a place it shares with longing and desire.

It is impossible not be be alarmed by the beauty of this work and its productive adherence to binary structure, and to conservative sex law. The men are in their place and have the power and legitimacy of the social order behind them while the woman is placed as other; mysterious, veiled, not in language, undistinguishable from her body, somehow deeply entwined in the process of representation. A political reading of the work could argue that the seductive beauty of Neshat’s sequences contribute to the repressive ideology of Islamic sex law, in the same way that Leni Riefensthal’s idealised Olympians contribute to an ideology of the Master race. Yet somehow the restrained and paired down visuality of Neshat’s work makes for a strange counter thought. If difference can be so clearly rendered then what is it that is really being said? Does the surface concur with a political message? Is the surface, which seems to echo with religious dogma, is this surface the meaning of the work? Difference is represented here as a visual register - a basic formal mechanism for recognition, like the lay-out of a chequer board. While the game to be played has a history and a specificity outside of our immediate grasp, it seems to offer not so much a symbolic proscription, a stripping down to male or female, black or white, but rather a productive delivery system for desire. Perhaps we could say that such clarity and formal opposition is structural to the production of meaning but at the same time does not determine meaning. We are thrown back to questions of passion and form and which is more curious of the other.