Sarah Kane In and On Media

Sarah Kane In and On Media

I

It is with a certain amount of surprise that I hear that Sarah Kane has been acclaimed in Germany as a proponent of the new realism. In Britain the first hostile reviewers of Blasted at the Royal Court were more likely to attack Kane for drifting away from the traditions of realism the Court has established since 1956. For instance, the reviewer for the Sunday Telegraph complained of the legion of "implausibilities" in the play, and Michael Billington claimed in The Guardian that "the play falls apart" because "there is no sense of external reality – who is exactly meant to be fighting whom out on the streets?"1 Billington also correctly pointed out the peculiar normality of Leeds in the middle of a civil conflagration (room service continues, football matches are played at Elland Road). This was not the least of their complaints, though, for the play’s various obscenities were what really energized the newspapers in 1995. And yet despite the poor press, Kane found powerful allies in Harold Pinter, Caryl Churchill and Edward Bond, who hailed her as an important new dramatic voice.2

I would like to suggest that to understand Blasted, we can indeed invoke its relationship to the Real, but to do so, we need to jettison the weak mimeticism by which the British reviewers understand the term 'realism'. Instead, it is more fruitful to approach Kane’s work by way of the Lacanian Real. Blasted, while hardly realist in the traditional sense, could be said to bring its audience to face the 'traumatic kernel of the Real'. Blasted, I therefore propose, can be best analysed by way of what has become known as 'trauma theory', as it is represented by Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub. The link between trauma theory and Blasted is hardly contentious. Trauma is a kind of brutalizing shock, and it is for submitting her audiences to exactly this, in heavy doses, that Kane has been both applauded and dismissed.

II

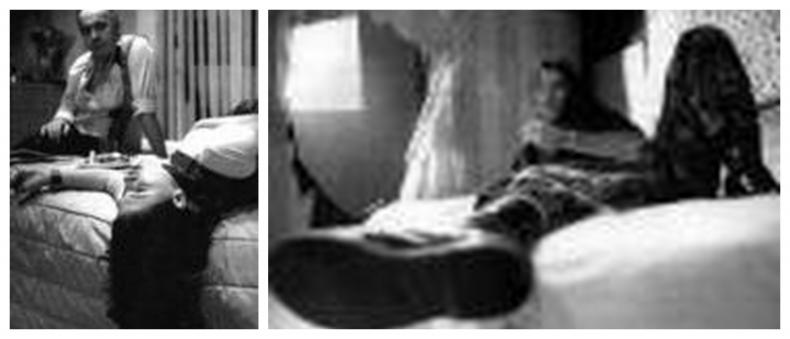

All three characters in Blasted seem to have undergone some form or other of traumatic experience. The soldier has both incurred and inflicted horrific violence during the course of whatever war is taking place and he continues to reenact in their full brutality these crimes. Ian, the journalist, has also been involved in some sort of atrocities, but he revisits his possible war crimes as phantasms, or rather, they revisit him. Finally, Cate, as a victim, is at once thrust into a compulsive repetition of her previous scenes of abuse, and yet, at the same time, resists the pattern of repetition and attempts to halt it.

Ian is perhaps the character who leaves the audience feeling most morally and ethically ambivalent. Charles Spencer, of the Telegraph, rather peevishly chastised the play for not telling him whether or not he should loathe or pity Ian, the dying, racist, journalist. It is much harder to pass judgment on Ian, because he is not forthcoming about what he has done in the past. Ian, like the soldier, is a perpetrator; but unlike the soldier, his status as victim is not clear, although his physical suffering in the present is graphically and repeatedly presented. It is no doubt this continuing spectacle of pain which elicits the sympathies of the uncertain spectator.

There are good reasons to assume that not everything that occurs on stage happens at the level of a single 'reality', but that at least some aspects of the civil war raging outside the hotel, and the arrival of the soldier, are in fact phantasms of Ian’s memory, externalisations of the previously unspoken. Are these inconsistencies simply poor plotting? There are hints in the text of the play that another interpretation is in order. For instance, Cate is never in the room at the same time as the soldier, and there is therefore no confirmation of his existence outside Ian’s imagination. The uncertain materiality of the soldier is hardly sorted out by the short shrift Cate gives him when she returns to the room: "She steps over the Soldier with a glance." (48) Furthermore, the actuality of the range of acts Ian carries out in Cate’s absence in scene five (masturbating, strangling himself, defecating on stage, eating the baby) is called into doubt by the staging (the lights come up and then go down for each 'vignette'), but most of all by the final miniature scene: 'He dies with relief.' He is alive enough in the next scene and we can only assume the death was a wish fulfillment.

III

The traumas from the past the three characters are encountering only come to them in fragments without ever taking on a complete form. It cannot be otherwise with trauma, Shoshana Felman would argue. It is in the very nature of trauma to resist being accounted for in a completely coherent or easily comprehensible way. If Blasted is disorienting as a spectacle, if much of what it shows its audience is "shrouded in mystery",3 it is because atrocities of this sort cannot be simply digested. Felman writes of

"a memory that has been overwhelmed by occurrences that have not settled into understanding or remembrance, acts that cannot be constructed as knowledge nor assimilated into full cognition, events in excess of our frames of reference." (Felman / Laub 1992: 5)

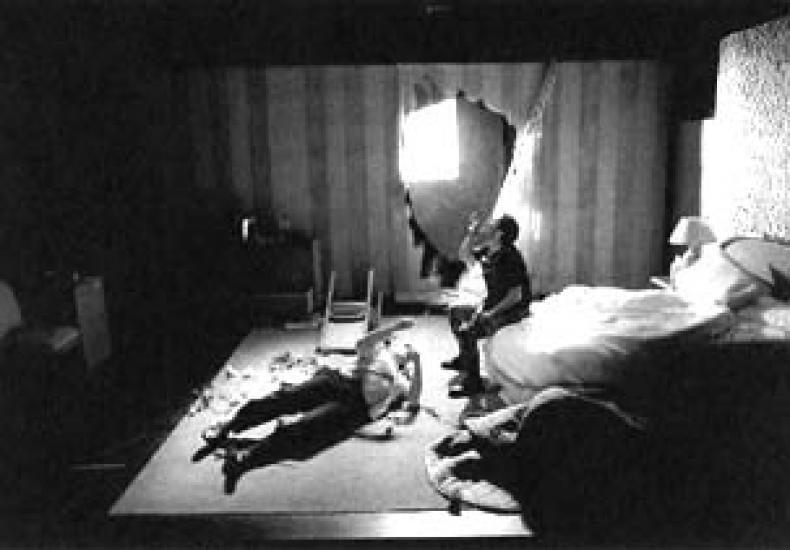

Certainly, in Blasted, there could not be a more literal exceeding of the frames of reference than the blast which opens a hole in the wall at the end of scene two. Trauma is not just a crisis in the memory of the traumatized subject, but a crisis in representation and narration. Felman uses the associated terms, witnessing and testimony, to describe the tortuous way in which trauma comes to be represented and/or narrated.

Felman has a very special understanding of 'testimony'. Felman wants to free testimony from its strict legalistic meaning: "testimony cannot be subsumed by its familiar notion […] texts that testify do not simply report facts but, in different ways, encounter – and make us encounter – strangeness" (Felman / Laub 1992: 7). She also makes a special case for the witness: "what constitutes the specificity of the innovative figure of the witness is […] not the mere telling, not the mere fact of reporting of the accident, but the witness’s readiness to become himself a medium of testimony – and a medium of the accident" (Felman / Laub 1992: 24). The dictionary, in contrast, gives the mundane "a person who gives evidence".

In Felman’s view, traumatic events are too problematic to be 'merely reported', and therefore traditional historical writing inevitably fails to capture the trauma adequately. Only literature, which proceeds indirectly, by narrative, metaphor, and other figures of speech, can approach trauma with enough subtlety. Only literature and art are capable of being self-conscious enough about their own impossible status as witness to do justice to extreme trauma:

"we underscore the question of the witness, and of witnessing, as nonhabitual, estranged conceptual prisms through which we attempt to apprehend – and to make tangible to the imagination – the ways in which our cultural frames of reference and our preexisting categories which delimit and determine our perception of reality have failed, essentially, both to contain, and to account for, the scale of what has happened in contemporary history." (Felman / Laub 1992: xv)

This position is effectively an adaptation of the theory of art and literature proposed by Russian Formalist critics who said that the task of literary language is to 'defamiliarise' an object or experience for the reader. Shklovsky says that "as perception becomes habitual, it becomes automatic" and that "The technique of art is to make objects 'unfamiliar', to make forms difficult ... Art removes objects from the automatism of perception".4 'Nonhabitual' and 'estranged' are the terms used by Felman and Laub, and the point they seem to be making is that certain events should never undergo an "automatism of perception"; they should always seem extraordinary and unfamiliar, lest they ever become 'normal' or 'ordinary'.

Blasted echos Felman’s doubts about the capacity for mere reporting to adequately account for the ethical weight and emotional charge of trauma. It is no coincidence that Ian is a journalist, and as such, responsible for witnessing on a daily basis. However, the traditional role of the journalist as the bearer of historical testimony is reduced here to the churning out of lurid clichés down a telephone:

"A serial killer slaughtered British tourist Samantha Scrace in a sick murder ritual comma, police revealed yesterday point new par. The bubbly nineteen-year-old from Leeds was among seven victims buried in identical triangular tombs in an isolated New Zealand forest point new par. Each had been stabbed more than twenty times and placed face down, comma, hands bound behind their backs point new par. Caps up, ashes at the site showed the maniac had stayed to cook a meal, caps down point new par. [etc]" (12)

The journalist writes of a horrific event from which he is removed by thousands of miles, in hackneyed language repeated in different variations in countless newspapers. There is a formula, Blasted is telling us, for rendering atrocities in a familiar, easily digestible fashion. The language for doing so is habitual and determined in advance: there is nothing strange about the murder of seven people. Journalistic haste – to meet a deadline, to capture a readership – only represses further the real kernel of a traumatic event.

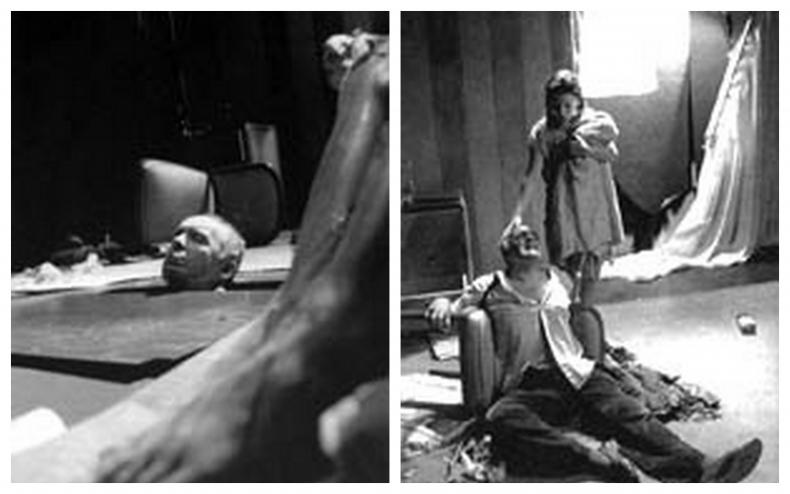

Ian is obviously a bad witness: not only does he make the events he reports seem routine and commonplace, but he is detached, both literally and symbolically, from those events. Blasted is the story of the revenge of events on the bad witness, culminating in the removal of his eyes. Only then can he see the necessity for witnessing. When Cate returns to him, he is insistent that she should take on the burden of the witness, that she should relate something to his son, Matthew:

Ian: Tell him – Tell him –

Cate: No.

Ian: Tell him –

Cate: No.

Ian: Don’t know what to tell him. (48-9)

The crisis in witnessing here is startling. The tale of Samantha Scrace rolled off the tongue - language here fails entirely: the attempt ends in silence. There is no simple way to assimilate what has happened into knowledge.

This crisis has been prefigured by the encounter between the soldier and Ian in the previous scene. The soldier has just told the story of his girlfriend’s rape and murder:

Soldier: Some journalist, that’s your job.

Ian: What?

Soldier: Proving it happened. I’m here, got no choice. But you. You should be telling people. (45)

The soldier has a fairly conventional view of the journalist’s responsibility to bear witness; but Ian’s sudden involvement in events demonstrates that the good witness, the one who is not detached, cool and objective, is often overwhelmed and therefore unable to bear witness.

Blasted implies that modern Britain is a society where potentially traumatizing events, such as rape and murder, are rendered inconsequential by the constant diet of them the press provides. In a language at once sensational and habitual, the reporting of 'limit events' is evacuated of any significance and real trauma is buried without a trace. Blasted, on the other hand, makes those events strange by presenting them so graphically, and in such an intimate environment. This is where theatre has a capacity to defamiliarise the sorts of images television and film bombards us with, breaking up the 'automatism of perception' with regards to horrific events.

IV

Finally, it is worth sparing a thought for those innocents who bore the first burden of witnessing Blasted – the London theatre reviewers. It is far too easy to reel off a string of quotations from the dailies and Sundays to show the sort of hysteria that broke out in 1995 in the wake of Kane’s debut. Although many of those first reviewers stuck to their guns and continued to lambaste Kane’s subsequent plays, others recanted and came around to Harold Pinter’s view that Kane’s 'was a very startling and tender voice […] appalled by the world in which she lived and the world within herself.'5 Unlike Pinter, those first reviewers were not able to ponder slowly and process some of the shocking scenes they had been subjected to. Instead, they are expected to be immediately eloquent about it, not only describing it, but passing judgment on the behalf of others (a readership whose expectations put even more limitations and pressures on the witness6). Like Ian, they possess only a habitual, hasty language, inadequate under the circumstances. The speed of the mass media forecloses the possibility of trauma’s gradual, belated emergence, long after the fact, and in difficult, attenuated forms. It is perhaps no coincidence, then, that 'trauma theory' has arisen in the wake of the global triumph of the mass medias, as a tentative attempt to slow them down.

- 1John Gross, 'Review' section, Sunday Telegraph, January 22, 1995, p. 6; Michael Billington, Guardian, January 20, 1995, p. 22. Billington subsequently changed heart about Blasted and apologised to Kane for dismissing it out of hand. See Simon Hattenstone, 'A Sad Hurrah', 'The Guardian Weekend', Guardian, July 1, 2000, pp. 26-34, 31.

- 2For an account of the media storm Blasted generated, and of the heated exchange of letters in the Guardian which followed, see Tom Sellar, 'Truth and Dare: Sarah Kane's Blasted', Theater 27:1 (1997), 29-34.

- 3Charles Spencer, The Daily Telegraph, January 20, 1995, p. 19.

- 4Victor Shklovsky, 'Art as Technique' (1917), Debating Texts: Readings in 20th Century Literary Theory and Method, ed. Rick Rylance (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987), pp. 48-56, 48-9.

- 5Quoted in Hattenstone, 'A Sad Hurrah', p. 31.

- 6I am thinking of poor Jack Tinker of the Daily Mail. Writing for that paper, what choice did he have but to entitle his notorious review 'The Disgusting Feast of Filth'?

Billington, Michael (1995) Guardian. January 20, 1995.

Felman, Shoshana and Laub, Dori (1992) Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History. London and New York: Routledge.

Gross, John (1995) 'Review' section. Sunday Telegraph, January 22, 1995, p.22.

Hattenstone, Simon (2000) 'A Sad Hurrah'. 'The Guardian Weekend'. Guardian, July 1, 2000, pp.26-34.

Kane, Sarah, Blasted, ####

Sellar, Tom (1997) 'Truth and Dare: Sarah Kane’s Blasted', in: Theater 27:1, pp. 29-34.

Shklovsky, Victor (1987) 'Art as Technique' (1917). Debating Texts: Readings in 20th Century Literary Theory and Method, edited by Rick Rylance. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp.48-56

Spencer, Charles (1995) The Daily Telegraph. January 20, 1995, p.19.