No 4: Tränen im Kino

No 4: Tränen im Kino

[english version below]

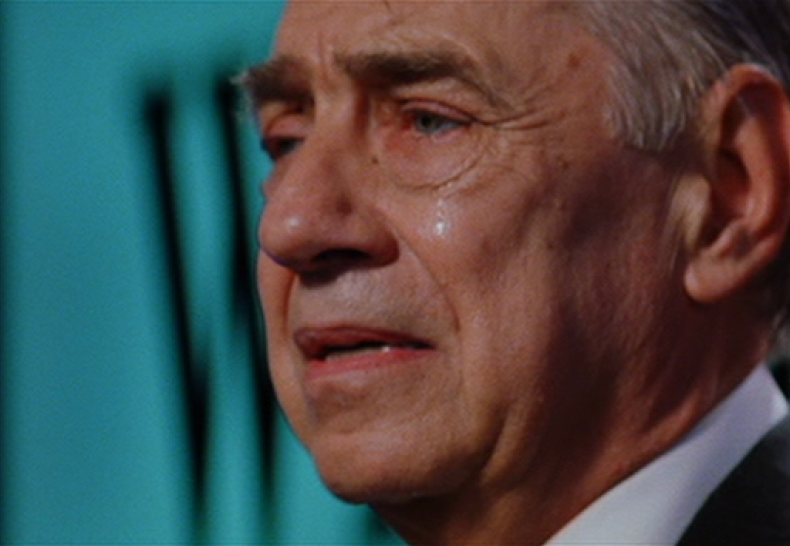

Wohl jedeR hat im Kino schon einmal geweint – aus Mitleid, Freude oder Rührung; über ein dramatisches Ereignis, eine tragische Figur oder auch einen mit Musik unterlegten Schwenk über eine Landschaft. Tränen zeigen sich in verschiedensten Ausprägungen – sie gehören zu unseren offenkundigsten leiblichen Kino-Erfahrungen. In Theorien des Kinos und Texten zum Film aber bleiben sie merkwürdig unberücksichtigt.

Nach dem Film begibt sich – inspiriert durch Gertrud Kochs Eröffnungsrede für das neue Kino "Arsenal" in Berlin – auf die Spuren der Tränen in Film und Medien.

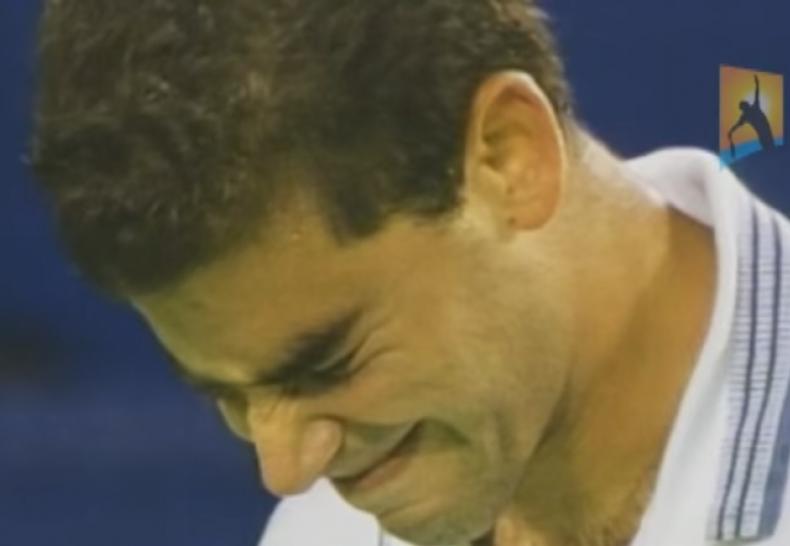

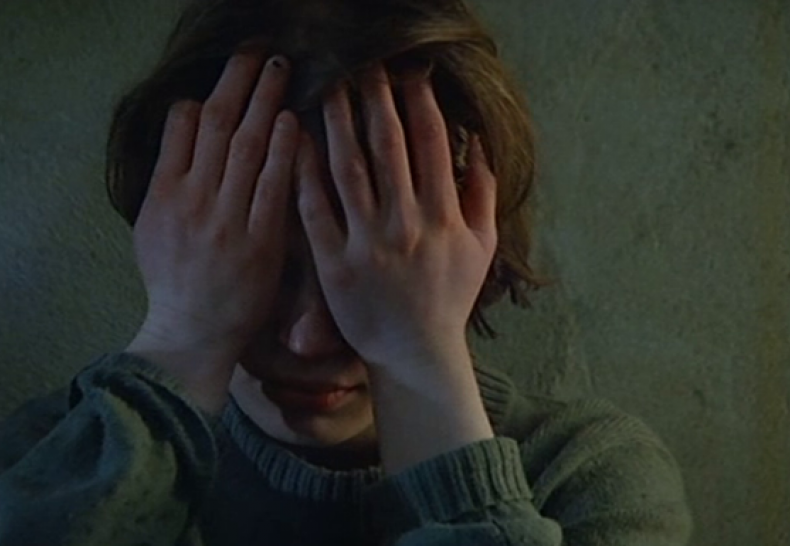

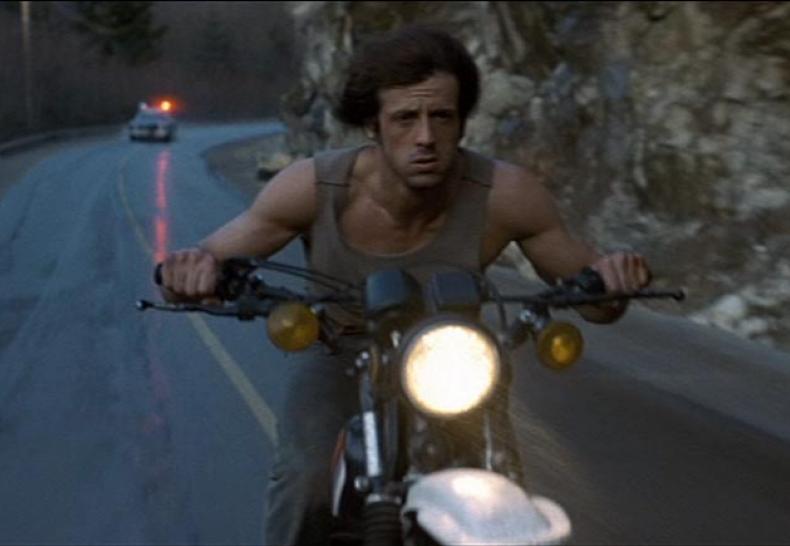

Tränen werden in vielfältigen Spannungsfeldern situiert: Wenn sie plötzlich an einem Ort stattfinden, an dem sie sonst nichts zu suchen haben, sind sie unerwartetes Ereignis eines Momentes. (Stauff) Sie erwecken gleichzeitig Genuss wie Peinlichkeit. Tränen stehen für Inkommunikabilität und werden im stillen Kämmerlein (oder im dunklen Raum des Kinos) vergossen; oder aber sie dienen gerade der Kommunikation, fordern zur Reaktion und zur Auslegung auf. Ist es das Leiden am unerfüllbaren Begehren, so dass Tränen zur Affekt-Abfuhr und Entleerung vergossen werden? (Decker) Oder aber füllen sie gerade eine im Zuge moderner Coolness entstandene Leere, indem sie Sinn und Eindeutigkeit geben? (Deterding) Im Weinen wird die Kontrolle über den Körper verloren, er fliesst über, entgrenzt sich und löst sich auf – gleichzeitig werden Tränen in der Performance der SchauspielerInnen bewusst ausgeführt. Tränen können als wahrhaftiger Ausfluss der Seele begriffen werden, aber auch als Fake, in dem uns etwas vorgespielt wird. Darum wecken sie manchmal distanzierte Neugier und das Bedürfnis, sie genauestens zu inspizieren und herauszubekommen, ob sie authentisch oder gefälscht sind. (Morsch) Wenn die Grenzen zwischen SchauspielerIn und Filmfigur durchlässig werden, ist nicht mehr klar: Spielt die Schauspielerin sich selbst oder eine Figur und wer weint eigentlich? (Streiter)

Sind wir mit den Tränen dem Besonderen von Film und Kino auf der Spur? Oder steht das melodramatische Kino nicht in einer Reihe mit anderen Medien der sentimentalen Unterhaltung? (Kappelhoff) Das Spezifische an den Tränen im Kino aber scheint zu sein, dass sie auf den Status kinematographischer Realität zielen. (Fliescher)

Wie erscheinen Tränen im Übergang vom Film zur ZuschauerIn – im Übergang von den Tränen zum Weinen? Macht uns das Mitleiden weinen – Mimesis also? (Döring) Besonders Kindertränen rufen unser Mitleid hervor. (Ott) Die Erinnerung, mit der das Weinen verknüpft ist, kann durch den Einsatz von Musik angerührt werden. (Rahman) Manchmal schlägt Weinen auch ins benachbarte Lachen um und man landet beim Affekt der Filmwissenschaft. (Schlüpmann) Das Weinen im Kino scheint kein einmaliges Ereignis, sondern mit demselben Film unendlich wiederholbar zu sein. (Weinerlebnisse im Tear Watch)

In den hier versammelten Beiträgen kann beobachtet werden, wie das Körper-Phänomen der Tränen in die vielfältigen Formen des Diskurses, in die Ordnung der Rationalität, eintritt. Manchmal ähneln sich die Tränen, manchmal sehen sie ganz unterschiedlich aus. In den Erlebnisberichten der ZuschauerInnen zum Beispiel scheinen sie auf andere Weise auf, als in den Annäherungen der eher wissenschaftlichen Beiträge. Zu fragen wäre, ob der Tränenfluss überhaupt angehalten, fixiert und durchdekliniert werden kann? Oder entzieht sich das Weinen dem Diskurs und blitzt nur manchesmal durch die Texte hindurch auf oder zieht wie ein Schauer kurz vorüber - wie die Tränen selbst?

Für die Redaktion Christine Hanke

No 4: Tears in the cinema

Editorial

Everybody cries in the cinema – out of pity, joy or simply because you have been moved by a dramatic event, a tragic character or even by a panning shot across a landscape combined with a particular piece of music. Tears well up in a variety of forms – they belong to our most tangible physical cinematic experiences. Both in film theory and other texts on the cinema, however, they remain strangely unrepresented.

Inspired by Gertrud Koch’s lecture on the occasion of the opening of the new Cinema "Arsenal" in Berlin, Nach dem Film has turned its attention to the traces of tears in film and other media.

Tears can be located in a variety of contexts: when they suddenly occur in a most inappropriate setting, they become an unexpected event, peculiar to the moment. (Stauff) They produce both pleasure and embarrassment. Tears represent a certain kind of incommensurability and are spilled in both the stillness of one’s own chambers (or rather in the darkness of the cinema); or they function as a tool of communication, beg a reaction and an interpretation. When the particular affliction is due to an unrequited emotion, tears fall as a means of affect regulation and bring about a restoration of an emotional equilibrium. (Decker) Or do they provide an antidote to the profound cynicism - and thus emptiness - of modern life, offering meaning and clarity? (Deterding) In crying, one loses control over one’s own body, it overflows, so to speak, its borders become less clear; however simultaneously tears belong to the repertoire of the actor. Tears can be taken for a marker of sincerity, a deluge that comes from the heart, or they can be faked. For that reason they oftentimes create a distance, a detached curiosity, and the need to examine them to discover whether they are authentic or counterfeit. (Morsch) When the border between the actor and the character become unclear, it also is no longer clear whether the actor plays him or herself, or a character – and who is actually doing the crying? (Streiter)

Are we onto something specific to film and the cinema, when we examine tears? Or is the filmic melodrama not instead a part of a long development in the realm of sentimental entertainment? (Kappelhoff) It seems however to be a specific feature of tears in the cinema, that they pertain to the nature of the particular status of cinematic reality. (Fliescher)

How do tears transfer themselves to the viewer – from a representation to an act in the audience? Does pity stir us to tears – that is, is it a mimetic event? (Döring) Do the tears of children produce a particular kind of pity? (Ott) The particular memories, which are bound up with tears, can perhaps be wakened by music. (Rahman) Oftentimes tears turn into laughter – and with that one arrives at the affect produced by the academic pursuit of film studies itself. (Schlüpmann) Tears in the cinema seem to not be an isolated event, but rather may be reproduced at will, when one chooses to watch a particular film, over and over. (real-life experiences with tears in Tear Watch)

One may observe how the physical phenomenon of crying has found a place in diverse discourses, taking the form of the rational, in the texts which have been collected here. Oftentimes there are similarities between types of tears – oftentimes there prove to be radical differences. For example, the reports of the viewers represented here in the Tearwatch section, tears find a different representation than they do in the more academic texts collected in this issue. It remains an open question, whether the flow of tears may be halted, fixed and examined? Or does crying become so intangible as to refuse its representation discursively, to only appear fleetingly in textual form?

Christine Hanke on behalf of the editorial board

(Translation: Robin Curtis)