The Eye of the Genius

The Eye of the Genius

Notes on Bentham and the Bulger case

On Friday February 12, 1993, on the far edge of Walton, in the suburb of Kirkby, on the distant outskirts of Liverpool, in North West England, Jon Venables was hurried out of his house by his mother. It was sometime shortly before nine in the morning and ten year old Jon was late for school. Carrying a note for his teacher, he began to make his way along the short walk to St. Mary’s Primary School. Having rounded Abigail Road, however, no longer in sight of his house, Jon quickly disappeared off into some nearby bushes only to re-emerge shortly afterwards without his school bag or books. Meeting up with his classmate Bobby Thompson, in the back alleys off Bedford Road, the two boys decided, like they had five times already that year, to skip school for the day.

Passing in and out of side streets and alleyways so as not to get noticed in their school uniforms, they walked down Breeze Hill, away from their homes and school in Walton. Idling beside the reservoir, they gradually made their way towards The Mons Pub, and then past Smiley’s Tyre and Exhaust Centre, onto Merton Road, across Stanley Road, over the Leeds and Liverpool canal, and finally into the rear entrance of the Bootle Strand Shopping Centre. It was a journey of about two and a half miles. Daring each other, along the way they stole some sweets, a couple of bars of chocolate, and a toy soldier from Clinton’s newsagents. At 12.34:34 seconds, precisely, they crossed the central interior concourse of the Strand shopping mall.

Several miles away in Kirkby, Denise Bulger was preparing to visit her sister-in-law Nicola Bailey, together with her two year old son, James. Leaving her flat, the two of them walked the short distance to Nicola’s small maisonette, where after eating a quick lunch, James played with Nicola’s younger daughter Vanessa. After lunch, at around 2.15, Nicola and Denise decided to drive the two children to the Strand Shopping Mall so that they could buy them both some new clothes at T. J Hughes’ Department Store. At 14.30:34 seconds precisely, Nicola’s burgundy Ford Orion entered the Strand multi-storey car park.

Jon and Bobby meanwhile were darting in and out of the Strand’s various shops. At Dixons electrical store they played on the computer games, in Tandy’s, after a few precautionary glances, they stole a pack of double A batteries, in the Bradford and Bingley Building Society they messed around on the chairs, until asked to leave, in Rathbones, the bakers, they pinched a pen from the counter, in Tesco’s the supermarket they sneaked some cartons of yogurt and milkshake under their coats, in Woolworths they ate a few chocolate dips and iced gems from the sweet counter, in Toymaster they stole two small tins of enamel paint, one bronze the other azure blue, with which they started to kick around the upper gallery, until the blue began to seep out onto the floor. Bored, they then started to fool around with the fire hydrant behind the main square.

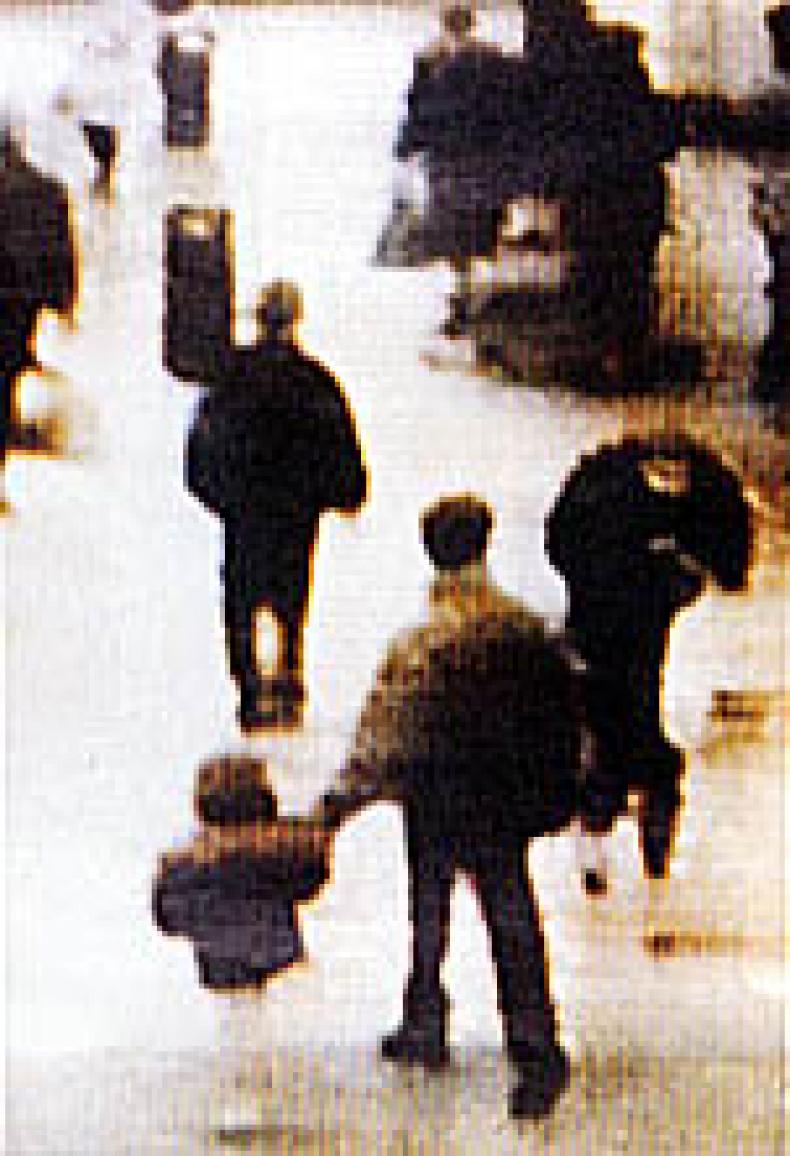

After coming out of T. J Hughes’ carrying several bags of clothes, Denise and Nicola, and the two children, walked into A. R. Tym’s Butchers. The time was exactly 15.37:51 seconds. While his mother was deciding what to get, James drifted back towards the entrance of the shop. At 15.38:55 seconds he stood alone outside the butchers, his attention fixed upon a smoldering cigarette. One minute and twenty-nine seconds later Denise appeared outside the butchers looking for her son. A further one minute and five seconds later James was on the upper level of the mall, talking with Jon Venables and Bobby Thompson. At 15.42:10 seconds Denise and Nicola entered the adjacent department store looking for James. Immediately below them though, exactly twenty-two seconds later, he was walking hand in hand with Jon Venables, towards the exit. At 15.43:08 seconds, the three boys left the mall through the main entrance.

Following a circuitous route across side streets and main roads, along the canal footpath, and beside the single track railway line, Jon and Bobby led James Bulger back towards Walton. When James began to cry and ask for his mother, he was punched and kicked, and forcibly dragged along the road. At exactly 16.49:09 seconds they passed the AMEC Building on Oxford Road. Over the course of the next hour, a number of people noticed the three of them but no-one stopped to ask what they were up to. At around 5.30, at the junction of Cherry Lane and Church Road West, they clambered up the grassy embankment of the railway line, and crawled through a small hole in the chain-link fence, down onto the line itself. There, concealed from view, and in the growing darkness, they splashed the blue azure paint over James’ face, and then proceeded to hit him repeatedly over the head with bricks and an iron bar. They then stripped him before finally laying his lifeless body across the railway tracks. A passing goods train, some hours later, separated James’ torso in two.

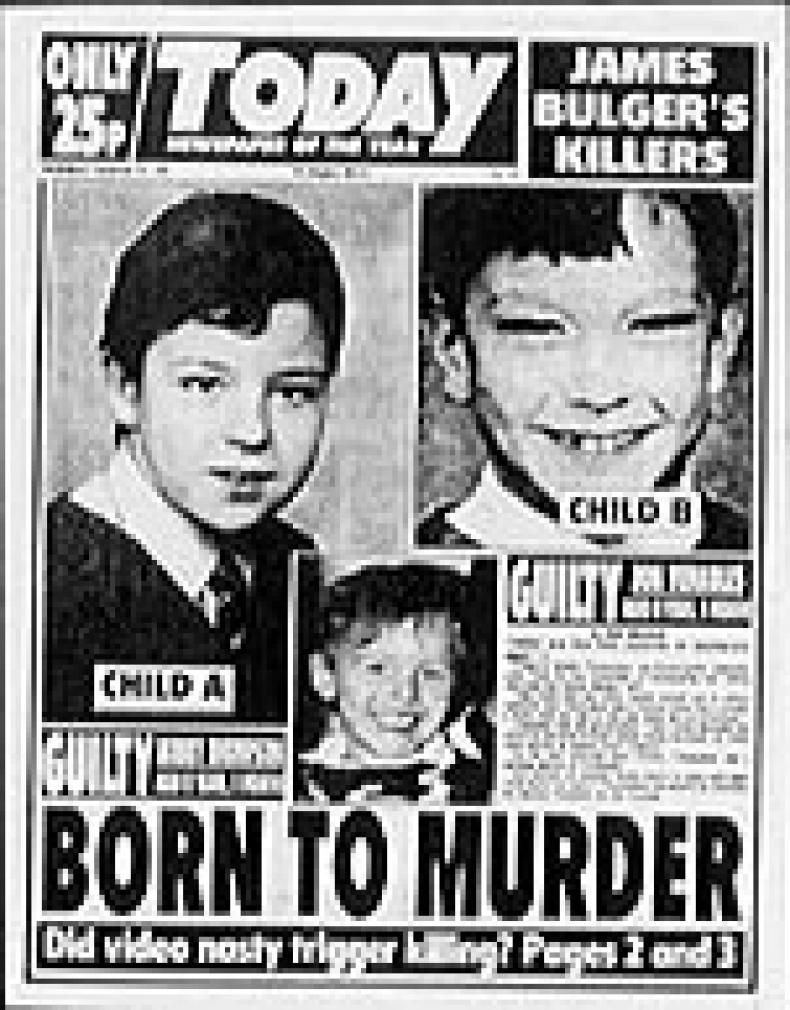

On Sunday February 14, two days later, at around 3.15 in the afternoon, James’ body was discovered by a group of boys playing on the line. The following day, amongst a crowd of mourners, Bobby Thompson himself, hand in hand with his mother, could be seen on a local television news bulletin, placing a single red rose on the site of James’ murder. Alerted by a neighbour, who noticed blue paint on his jacket, the police arrested first Jon Venables and then Bobby Thompson, three days later on Thursday February 18. After two days of questioning, on Saturday, February 20, at 6.15 in the evening, both boys were formally charged with the abduction and killing of James Bulger. In the courtroom of Mr. Justice Morland, in nearby Preston, nine months, and four days later, Jon Venables and Robert Thompson were found guilty of "acts of unparalleled evil and barbarity,"and were sentenced to be held for eight years in a secure unit. A raised wooden platform had to be added to the base of the witness box so that eleven years old Jon and Bobby could be seen receiving the verdict. A month later, the Lord Chief Justice upped the sentence to ten years. A further month later, Michael Howard, the Home Secretary, increased the sentence again, to fifteen years. Justifying this decision some short while later, Prime Minister John Major reiterated, "[...] that society needs to condemn a little more and understand a little less."1

Shopping and surveillance

"You may consider that no part of the Empire is without surveillance, no crime, no offence, no contravention that remains unpunished, and that the eye of the genius who can enlighten all embraces the whole of this vast machine, without, however, the slightest detail escaping his attention". J. B. Treilhard, Motifs du code d’instruction criminelle (1808)2

The reason, of course, that the events leading up to the abduction and murder of James Bulger are so precise, so exact, down to the nearest second, is because it was captured on an almost all-seeing system of video surveillance cameras. When Jon Venables and Bobby Thompson first appeared in the Strand Shopping Mall, their entrance was recorded on Camera No. 8. When Nicola and Denise drove into the car park, no-one but Camera No. 16 saw them. From the tape in the Bradford and Bingley Building Society Jon and Bobby could be seen jumping around on the chairs. In Woolworths, there they were stealing and eating sweets. Their passage from outside the butchers to exiting the mall was tracked by Cameras 6, 10, 3, and 8. Outside even, on Oxford Road, they were seen because of cameras mounted on the facade of the AMEC building, protecting its car park twenty-four hours a day. The documentary of their movements loses its precision only in those spaces where the boys could not be seen. Crucially there were no video cameras overlooking the railway line. There is then no conclusive visual evidence to support Jon Venables’ claim that Bobby Thompson did it, or Bobby’s, that it was all Jon’s idea.

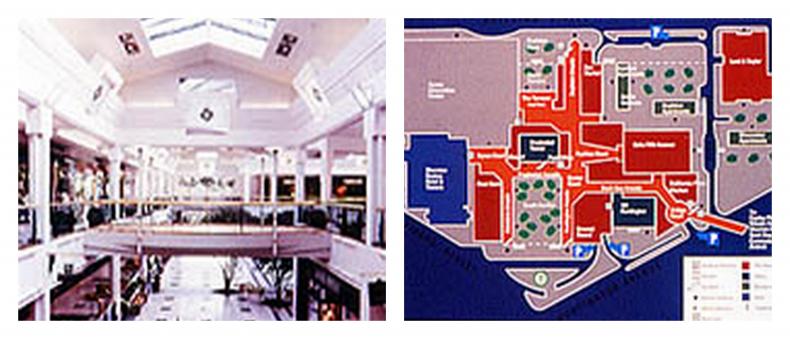

Because this final resting place of James’ remained unseen by the public at large, the Strand Shopping Mall, rather than the railway siding, became, for the media and public alike, the representative place in which two children murdered a child. In the days immediately following the murder, while the streets outside remained busy, inside the Strand there were but a handful of people walking around. Amid an atmosphere of funereal calm, children were physically bound to their parents. Mothercare reported that children’s reins, popular in the 1960s, were increasingly back in demand, with over seventy orders having been placed at its branch alone. Architecture suddenly found itself ally to a terrible crime. In defining the nature of this architecture, and of its role as backdrop to an infantile murder, an interesting double precedence, to the model of America, and of American society, emerges. The Strand had opened as a concrete exterior precinct of shops in 1968, one of the first of its kind, but over the next twenty years, the novelty and innovation it offered was increasingly lost beneath patinas of vandalism and disrepair. In 1989, encouraged by the self-help dictates of Thatcherism, a group of local businessmen decided to redevelop the precinct along the lines of the suburban American mall – the whole space was roofed over, light filled atria illuminated the once darkened recesses, much of the concrete disappeared behind shiny aluminium cladding, and small, benched squares were situated in various quarters. To enhance the sense of comfort and security, a public address system was installed, through which piped music was played, and the occasional admonishment delivered. There were also sprinklers, smoke detectors, and a closed circuit television system: 20 cameras, each recording onto video tape a still image every 3 seconds. In the competition to rename the centre, "Little America" was narrowly defeated by "The New Strand." Following the murder itself, much of the tabloid, populist press, were quick to point out the appropriateness of this setting. This was not an English shopping arena but an American one, and as if related, this was not an English crime, but one typically American – these things happen all the time there, but never here – Jon Venables and Bobby Thompson had obviously watched too much bad, violent, American television.3

Bentham's panopticon

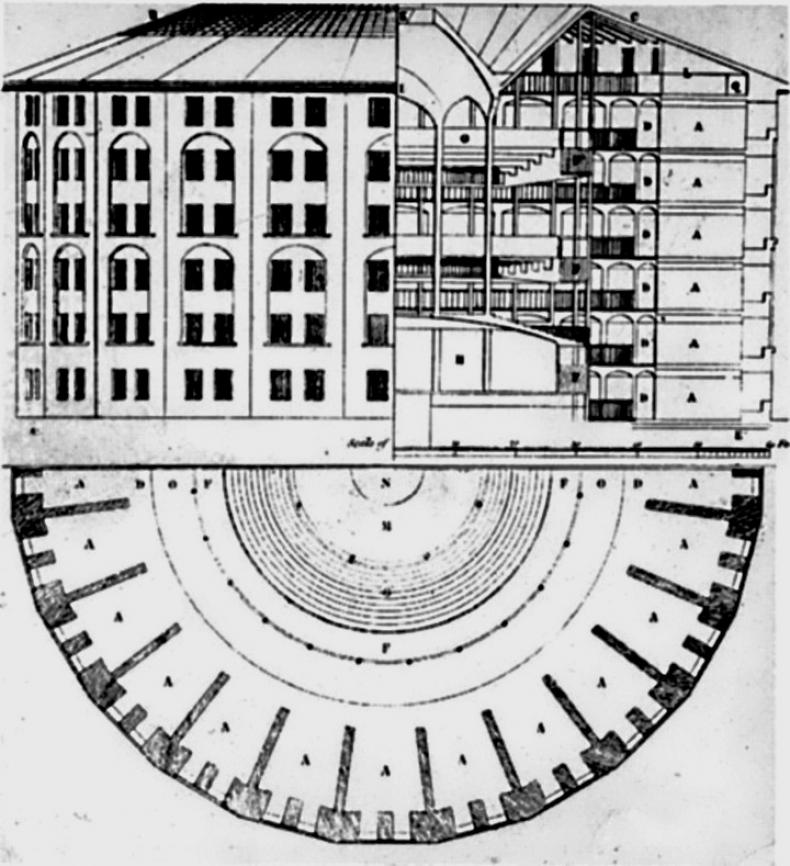

In the allocation of blame however, an architecture significantly closer to home, appeared to have gone unnoticed. If precedence were the only criteria, a more accurate and fitting name for the newly redeveloped Strand Shopping Centre, would have been "Little England." The interior space of the Strand as it appears to us now, and how it was depicted in reports and bulletins immediately following the murder, seems to have a distinct English ancestry. More than the shopping malls of late twentieth-century suburban America, its principal architectural antecedent can be found in the prisons of late eighteenth-century urban England; not however, those Dickensian dungeons of Newgate Jail and the Tower, but specifically the new model prison as envisaged by the philosopher and social theorist, Jeremy Bentham. Alluding to its infinite applicability, Bentham announced the arrival of his idea for a prison in a "letter" dated 1787:

"To say all in one word, it [the 'Inspection House' or 'Panopticon' prison] will be found applicable, I think without exception, to all establishments whatsoever, in which, within a space not too large to be covered or commanded by buildings, a number of persons are meant to be kept under inspection. No matter how different, or even opposite the purpose: whether it be that of punishing the incorrigible, guarding the insane, reforming the vicious, confining the suspected, employing the idle, maintaining the helpless, curing the sick, instructing the willing in any branch of industry, or training the rising race in the path of education: in a word, whether it be applied to the purposes of perpetual prisons in the room of death, or prisons for confinement before trial, or penitentiary houses, or houses of correction, or work-houses, or manufactories, or mad-houses, or hospitals, or schools."4

Allowing for, and in many ways, anticipating its suitability for a number of building types, Bentham confidently saw his proposal as heralding a new architectural standard. Two centuries on, perhaps though, even Bentham would have been surprised to find a version of the Panopticon occupied not by the criminal, the sick, and insane, but by shoppers, by Mothercares and Woolworths. The principles of its design, however, consistently remained the same. As described by Bentham, this universal idea consisted of a ring-like building of several stories, surrounding a central tower. The tower was punctured by windows opening out onto the inner side of the peripheral mass of rooms or cells. These openings were aligned with those of the individual cells, each of which had two windows, an inner one, and a larger outer one. The entire cell would be backlit from the rear window, allowing an observer in the tower to survey fully the inhabitants of each cell. Reversing the antiquated model of the dark and swarming dungeon, everything in the Panopticon would be perfectly individualised and constantly visible. The one exception to this overt-illumination, of course, was the central tower. Defined by Bentham both as an "utterly dark spot,"5 and a "lantern" (but a lantern which absorbed rather than radiated light), great pains were taken to render the supervisor invisible to those being surveyed. To overcome this problem, he envisaged not only venetian blinds on the windows of the tower, but in its interior, partitions were to intersect the space at right angles. The success of such devices was crucial to the workings of the whole plan, as any slight noise or gleam of light would betray the presence of the supervisor. Power in this regime therefore was simultaneously both visible and unverifiable. In the Panopticon, inmates are seen without seeing the one who sees them. Seeking to reform the design of the prison, Bentham had inadvertently discovered the omniscient authority of an architectural divine.

In his Architectonography of Prisons (1829) the French architect Louis-Pierre Baltard wrote that "The English bring into all their works the genius for mechanics which they have perfected, and they thus want their buildings to function like a machine worked by a single motor."6 Michel Foucault’s famous study, Discipline and Punish (1975), which heralded the rediscovery of the model of the Panopticon, quotes from the same Baltard passage. Seeking though to establish the prison as a model more fundamentally of political, rather than architectural, control, he maintained that the Panopticon "must not be understood as a dream building: it is a diagram of a mechanism of power reduced to its ideal form: [...]: it is in fact a figure of political technology that may and must be detached from any specific use."7 However, as it manifested itself on the outskirts of Liverpool, in February 1993, this panopticon revealed itself as if through the machinations of some terrible nocturnal fantasy. Setting the tone for all subsequent reactions, the first public announcement by the family of James Bulger was that the whole event had been "like a dream."8 In this dream, the Strand seemed to have distorted itself into the nightmarish lair of an ultimate immorality. Images from the world of fairy-tale were borrowed, presenting the centre as some kind of witch’s castle, as a looming dungeon, enshrouded in perpetual shadow. Conflating his Conrad with his Grimm, former Home Secretary, Kenneth Baker, observed, synoptically, that "When a young, innocent toddler is killed in a brutal way, then you are beyond the edge of evil, you are in the heart of darkness."9

Waking up from this dream however, the Strand as it existed physically, in reified, built form, cast off this imaginistic gloom. In this concrete state, lightness, rather than darkness, provided the essential visual characteristic. Perhaps, though, to be exact, it was aluminium, as distinct from concrete, that defined its luminescence. Like Bentham’s Panopticon, the architectural rhetoric of the mall, required that everything inside be flooded in light. Sold through the ubiquity of their atria, these malls sought to ignore an obvious paradox, in creating an inside "lighter" and "more airy" than the outside. The built structure of the shopping centre also shares many of the elements of the earlier, Bentham model: a large, enclosed space of multiple levels, with a periphery of sub-divided shops and stores. Like the Panopticon too, its architecture is organised, fundamentally, as a mapping system, as an arrangement of bodies in space. Providing a visual, almost totemic image of this arrangement, the exploded, usually colour-coded, axonometric plan of floors, has become in many ways, the symbolic emblem of the mall. "You are Here" and the accompanying arrow is the required greeting one gets on entering any mall.

The one omission, of course, to this Benthamite architecture of light and power, was the central control tower. No looming gazebo stood in the middle of the Strand. But although the structure itself had disappeared, the importance of its role had been retained: in its late twentieth-century incarnation, the shopping mall panopticon had merely refined the art of inspection. In the closed-circuit video camera, technology had provided an alternative, electronic apparatus for surveillance. The eye of the genius was now made only in Japan. At the Strand shopping centre there were twenty of these video cameras, placed at elevated, strategic points so that no one area would remain unseen. In a newspaper report, in the wake of the Bulger murder, entitled, "Big Brother becomes the citizen’s best friend," Chief Inspector Bob Pattison, of the Newcastle police, spoke of the advantages of this video technology. "The cameras," he said, "give an average P.C [police constable] on the street sixteen pairs of eyes, and yet they don’t take rest breaks, don’t need to go to the toilet, and don’t take annual leave."10 Diligent, uncomplaining, and in need of no relief, these networks of artificial lenses could oversee spaces more thoroughly and efficiently than any eye. Hovering high above like some all-seeing/unseen divine, the camera held the promise of perfect peace and order. A "vision" anticipated two hundred years earlier in Bentham’s conclusion to his study; " – morals [will be] reformed, health preserved, industry invigorated, instruction diffused, public burthens lightened, economy seated as it were upon a rock, [...] – all by a simple idea in architecture."11

Waking up from this dream however, the Strand as it existed physically, in reified, built form, cast off this imaginistic gloom. In this concrete state, lightness, rather than darkness, provided the essential visual characteristic. Perhaps, though, to be exact, it was aluminium, as distinct from concrete, that defined its luminescence. Like Bentham’s Panopticon, the architectural rhetoric of the mall, required that everything inside be flooded in light. Sold through the ubiquity of their atria, these malls sought to ignore an obvious paradox, in creating an inside "lighter" and "more airy" than the outside. The built structure of the shopping centre also shares many of the elements of the earlier, Bentham model: a large, enclosed space of multiple levels, with a periphery of sub-divided shops and stores. Like the Panopticon too, its architecture is organised, fundamentally, as a mapping system, as an arrangement of bodies in space. Providing a visual, almost totemic image of this arrangement, the exploded, usually colour-coded, axonometric plan of floors, has become in many ways, the symbolic emblem of the mall. "You are Here" and the accompanying arrow is the required greeting one gets on entering any mall.

The one omission, of course, to this Benthamite architecture of light and power, was the central control tower. No looming gazebo stood in the middle of the Strand. But although the structure itself had disappeared, the importance of its role had been retained: in its late twentieth-century incarnation, the shopping mall panopticon had merely refined the art of inspection. In the closed-circuit video camera, technology had provided an alternative, electronic apparatus for surveillance. The eye of the genius was now made only in Japan. At the Strand shopping centre there were twenty of these video cameras, placed at elevated, strategic points so that no one area would remain unseen. In a newspaper report, in the wake of the Bulger murder, entitled, "Big Brother becomes the citizen’s best friend," Chief Inspector Bob Pattison, of the Newcastle police, spoke of the advantages of this video technology. "The cameras," he said, "give an average P.C [police constable] on the street sixteen pairs of eyes, and yet they don’t take rest breaks, don’t need to go to the toilet, and don’t take annual leave."12 Diligent, uncomplaining, and in need of no relief, these networks of artificial lenses could oversee spaces more thoroughly and efficiently than any eye. Hovering high above like some all-seeing/unseen divine, the camera held the promise of perfect peace and order. A "vision" anticipated two hundred years earlier in Bentham’s conclusion to his study; " – morals [will be] reformed, health preserved, industry invigorated, instruction diffused, public burthens lightened, economy seated as it were upon a rock, [...] – all by a simple idea in architecture."13

An architectural failing

In those late February days of 1993 however, the optimistic promise of a society morally pure, was quickly forgotten. The simple idea in architecture at the Strand had turned out to be no social panacea. Nurtured amongst the squares and walkways of its interior were the values not of reform, honour and trust, but contempt, violation and criminality. While cameras looked on, morals appeared to have been abandoned, health, and more importantly life, terminated, and public burthens worsened. The panoptic system that Foucault had described as a house of certainty and security, had seemingly been reversed into a house of danger and confusion. Consistent with the scientific language of its invention as an "Elaboratory" (Bentham’s alternative name for his design), the abduction and murder of James Bulger appeared to be an architectural failing, of an experiment gone wrong.

Precipitating this failing, two ten year old boys had literally stolen a young child right from under the eyes, if not the nose, of a system designed to instill peace and order. Buoyed by a child-like sense of their own invincibility, Jon Venables’ and Bobby Thompson’s act represented a fundamental challenge to the panopticon; daring to see if their actions would go unchecked, they called the bluff of an architectural system that purported to see everything, but that was perhaps suffering from a certain myopia.14 In the fundamental asymmetry of Bentham’s design, the two boys had discovered an obvious blind-spot. Like the original Panopticon, the Strand was arranged around an axial visibility, and a lateral invisibility: a controller (or camera) could see the inmates (or shoppers), but the inmates (or shoppers) could not see one another. Clearly playing itself out on video tape between 15.42:10 seconds and 15.43:08 seconds, the cameras at the Strand saw and recorded the separate movements of Denise Bulger, up above, and James Bulger, down below, but neither mother nor child could see each other. Exploiting this lacuna, Jon Venables and Bobby Thompson could walk calmly away, seen only by one set of eyes.

A more obvious area of blindness, of course, was found outside the mall. As darkness fell, the two boys led James Bulger to the one place they knew where nobody would see them. With no electrical lighting, no overhead cameras, and accessible only through a gap in a fence, the railway siding offered a zone of both complete protection (for the killers) and complete danger (for the victim). Despite, however, this being the site of Venables’ and Thompson’s principal crime – of the horrific killing of a child, it was back in the space of the mall, and the abduction of a child, rather than his murder, that seemed to hold a greater sense of horror. More than their discovery of pockets of invisibility, a higher level of cunning was evident in their careful dismantling of the assumption that seeing is synonymous with controlling. Through their repeated shop-lifting, the boys appeared to be testing out the system of surveillance; checking to discover not whether they were being seen or not (for they could see the cameras like everybody else), but whether anyone was actually looking through the camera, and able to act upon what they saw. In confidently walking away with James Bulger, hand in hand, they had metaphorically penetrated the space behind the camera, having turned on the lights on a once "utterly dark spot," and discovered that no-one was there after all. But by ultimately revealing an absence, Jon and Bobby had also inadvertently exposed an existential dilemma. To invoke a common theological analogy, the panopticon/video camera represents a secular parody of divine omniscience – that the observer, like God, is invisible. Significantly, the two boys tacitly reinforced this analogy, but in their skepticism they challenged the idea of there really being a God, of there really being an observer. In this way, perhaps together with abduction and murder, Jon Venables and Bobby Thompson were also guilty of a certain kind of atheism, of a fundamental lack of faith. As Luis Buñuel once remarked, "Thank God I’m still an atheist."

Parenthetical to these questions of enlightenment, of exposure, of extremes of light and dark, are also interesting resonances of the Freudian concept of the "uncanny." Famously defined by Schelling as "the name for everything that ought to have remained [...] secret and hidden but has come to light,"15 Freud used the concept to elucidate (among other things) upon a theory of light and dark space. For the imaginary horrors of ghosts and ghouls, darkness, he argued, seems to represent a natural habitat, of an arena unseen, but assumed to shelter an unspeakable presence. Citing literary examples, these phantoms are to become uncanny only when brought out into the open, away from their shadowy lair – E. T. A. Hoffmann’s nursery-tale bogey figure, the Sandman, haunting the susceptible Nathanael, in appearing to manifest himself in his waking, everyday life. Seen in this light (so to speak), Jon Venables and Bobby Thompson had induced an essentially uncanny act – they had brought out into the open, something that should have remained perpetually in darkness; dragging a non-existent controller out into the light. The fact that there was nothing after all, no ghost in the machine, lurking in the gloom, merely reinforces this uncanny. As a kind of adult reassurance delivered by two children, they "enlightened" and reasoned with a believing, gullible audience, not to be deceived by the power of their imagination.

Advanced computer technology (Holmes versus H.O.L.M.E.S.)

One of the ironies of the Bulger case, was that in this "enlightenment" the two boys (or for Bentham, inmates) were far more successful than the supposedly all-seeing luminescence of the surveillance system itself. Recorded onto tape leaving the mall, the video footage of the abduction of James Bulger held the promise of an image clear and easily identifiable. But the resultant still, distorted and heavily pixilated, revealed nothing of any real clarity. A small child could be seen hand in hand with a shadowy figure, but details as to the identity of this figure – of age, of height, of appearance, and clothing, remained a mystery. Exposed as a high-technology which peered decrepitly into space, the eyes in which the Strand had invested its trust, had in reality seen very little at all. In an attempt to improve upon their resolution, police sent the tapes from the Strand to be "enhanced." Duncan Campbell in The Guardian newspaper reported that the computer systems of NASA, the RAF, and IBM’s Scientific Research Centre had been utilised in an effort to clarify the images. As a technological solution came to the aid of an technological failure, the tapes were translated from analogue to digital, and then manipulated using advanced image processing programmes.16 A final image was produced, coloured and somewhat refined, but still revealing little of anything new.

Despite these failings, in the weeks of the police investigation, further advanced computer technologies were utilised in the hunt for James Bulger’s killers. In particular the Central Analytical Team Collating Homicide Expertise Management was put to use, as was the Home Office Large Major Enquiry System, a somewhat convoluted pair of titles for two computers, but ones constructed less for purposes of literary finesse than for the acronyms they produced; C.A.T.C.H.E.M and H.O.L.M.E.S. But while these systems processed information, more conventional, physical leads were being followed. If, as Walter Benjamin has suggested, living "means to leave traces,"17 then for sure, to murder is to leave a trail. Splashing paint on the body of James Bulger, Jon and Bobby had inadvertently stained their own hands, clothes, and shoes, allowing for a trail of azure blue drips to be followed, and their identities revealed. (Jon Venables was arrested after a neighbour noticed these blue stains on his jacket). A fictional detective would have simply pulled out a magnifying glass, and after a short pursuit, announced, "I therefore conclude that the murderer is . . . ." The irony of this story is that Holmes, one feels sure, would have solved the case of James Bulger, but H.O.L.M.E.S ultimately failed to do so.

If, as was the case then, that the strategically placed cameras and accompanying computer systems were unsuccessful in their prevention of a crime, and even in their catching of a criminal, what role was it that they sought to carry out? Millions of pounds of hi-tech equipment cannot possibly have been invested in the production simply of an irresolute blur. The timing of their utilisation, perhaps though, offers an explanation. Providing images of an abduction after an abduction, the electronic panopticon seems involved less with the prevention of crime, than, in a way, with its celebration. As the principal engine in the manufacture of emblems of criminality, it commemorated an act onto magnetic tape. The camera, true to its associations, saw everything in its lens as a performance: a show that subsequently played itself out in the newspapers, and on the televisions of every English home. Foucault’s observation that the society that Bentham envisaged was no longer one of spectacle but of surveillance had in effect been reversed.18 In the late-twentieth century, spectacle had regained control.

The spectacle of criminality

This pantomine-like quality of the electronic panopticon was not, however, merely a reflection of a late-modern voyeurism, but rather, it marked the development of an allusion manifest in its original prototype. In the metaphors he adopted to describe his proposal, Bentham would often resort to theatrical analogies. Writing in the postscript to his letters, he frequently referred to the inmates of his Panopticon as "actors," their cells as "theatres," and the surrounding architecture of the prison itself, a "back-lit scenery." Bentham even went so far as to suggest that the key member of every well-composed committee of penal law was the "manager of a theatre," who would naturally know how to attain the greatest effect from the staging of punishment.19 There is also something inherently theatrical about the principles upon which the Panopticon was based. According to Bentham, in his prison "the apparent omnipresence of the inspector" is combined with "the extreme facility of his real presence"; it is precisely the inspector’s assumed ubiquity that deters the prisoners from transgressing, sustaining perfect discipline.20 The oppositions of a real/apparent omnipresence, of a real/apparent punishment, and of a real/apparent suffering, "appear" in this way to permeate all aspects of his design. As in the theatre, one is led to believe in the fictional. The "being" that Bentham later addressed in his "Fragment on Ontology" was perhaps therefore, one costumed and performing a role.

With the introduction of the security camera, in place of the control tower, this spectacle of criminality was both refined, and at the same time, made available to a far wider audience. Crimes, like the abduction of James Bulger, could not only be recorded as they happened, but could subsequently replay themselves out at the touch of a button. As if standing in the wings of every murder scene, is a megaphone wielding director, prefacing each violation with the axiomatic words, "Lights, Camera, Action." Rather than "a trap," as Foucault suggested, visibility has now become a stage.21 The extent to which surveillance can provide this entertainment is revealed by the increasing proliferation of "true-crime" shows on television. Constituting simply the highlighted footage from security video tapes (from banks, stores, and from the front of police cars), real hold-ups, real assaults, and real chases, have proved compulsive viewing. There is though, in this voyeurism, something of a medievalist tendency. We no longer attend public hangings, floggings and general torturing, of the sought Foucault introduced his Discipline and Punish, but rather better, we can now attend the crime itself. Watching a robbery on tape, is almost as if one was actually there. Significantly, through these simulations, a long established tradition appears to have been reversed. From the ancient Roman feeding of criminals to the lions, to the French revolutionary guillotine, to Bentham’s transparent prison, punishment has always been available for public viewing. But now, however, it is the crime, rather than the punishment that we see. Here is Jon Venables and Bobby Thompson leading James Bulger away, but where they are now, nobody knows. A court order has insured that the whereabouts of the boy’s prison remains a firmly kept secret.

Jamie Wagg

In May 1994, over a year after James Bulger’s death, artist Jamie Wagg exhibited two pieces at the Whitechapel Gallery in London. Using the Bulger video footage they were entitled, History Painting: Railway Line and History Painting: Shopping Mall, and depicted the two sites of James’ murder and abduction. Three weeks after the exhibition opened, the tabloid Daily Mirror newspaper, in particular, launched a scathing attack on both the artist and the artwork. Involving the Bulger family, they quoted James’ grandmother as saying, "How can you call that art? I just call it sick." Also questioning the exhibits’ claims to the status of art, James’ uncle announced that the pieces were just two "blown-up photographs and that is definitely not art." Fueling the Daily Mirror’s delicate sense of outrage, was the idea that Jamie Wagg appeared to be profiting from the death of James Bulger – highlighting the price attached to the two works, £2,235, it labeled the whole endeavour "SICK"22 – but was at the same time, seemingly oblivious to the fact that the very same images had been printed all over the Daily Mirror front pages, together with the front pages of every other English newspaper following the murder, in an effort, fundamentally, to sell more copies, to boost circulation.

Both during and after the event, in this way, a single image had sustained an incredible power over its audience; inducing through its publication, feelings of outrage, of disgust and violation. The intensity of these reactions can perhaps, in part, be explained by the ambiguities offered by the image itself. As Mark Cousins has noted, the original, and most widely used photograph of the three boys illustrates a scene not of horror but of harmlessness, or normality, of nothing yet wrong. It is of a toddler seen, held not only by a protective hand, but by the gaze of closed-circuit safety.23 As if advertising these associations, the word "MOTHERCARE" proudly offers an inscribed maternal caveat to the whole scene. Once reprinted under the headlines of child murder, however, these now totally inappropriate slogans, enraged a captive public. Not care but the apparent carelessness of mothers, at 15.42:32 seconds, the wrong hand was leading James Bulger to his death.

Childhood and memory

Writing on the history of family life in his Centuries of Childhood, Philippe Ariés has noted that from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, parents have consistently been compelled to record details of their children’s names and dates. Documented in annuals or physically carved onto personal belongings, "people," he observed, have always "felt a need to give family life a history by dating it."24 This need, it seems, is continuing. Like albums and records books, or even like a doorway decorated with the escalating horizontal markers of a child’s growth, the photograph of James Bulger historicised his life. Held within its blurred, pixilated frame, his brief few years were remembered. More than its dating, however, the iconography of the image, has additional historical antecedents. Continuing his study, Ariés added that in the history of infant portraiture, two distinct artistic traditions have evolved. Appearing initially in the Middle Ages, the first of these was the putto or naked child; an image that quickly spread across Europe on religious tapestries before finding a celebratory embrace in Titian’s Triumph of Venus. The alternative tradition was that of the dead child; a commemorative funereal effigy adorning tombs and paintings from the sixteenth century onwards.25 The video still of the abduction seems, in many ways, to merge the typologies of these two art histories. Viewed after the event, the photograph shows James Bulger seen and alive, but it memorialises a now unseen child, about to be naked and about to be dead.

Providing a backdrop to this image, and of its associations, the space of the mall increasingly reveals itself as some kind of architectural mnemonic – an interior territory into which a number of distinct events, ideas, and histories have been inscribed. To walk around the Strand, in reality, or even in one’s imagination, passed A. R. Tym’s Butchers, passed Mothercare, and its surveillance camera, is to be reminded of the details of the story of James Bulger. Perhaps as an inheritor to the ancient Greek Memory Theatres of Camillo and Quintillian, the Strand appears to us now as a space through which one remembers.26 Accessed through this retrieval are also other spaces, other territories, specific to the lives of children. The story of the murder of James Bulger unfolds like a fictional account of childhood fantasy. As its banal preamble, Jon Venables wakes up in a real world of alarm clocks and schools, but he soon leaves the everyday behind. Darting off into a nearby hedgerow, he emerges the other side, seemingly empowered and reinvented as someone else. Like the wardrobe of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, or Alice’s warren, the vegetation provides a gateway to a parallel world of adventure. Similarly, other apertures appear throughout the story: the grand ceremonial entrance of the Strand which framed the two boys’ entrance and the three boys’ departure, and the hole in the chain link fence, large enough only for small children to clamber through. Cast alternatively in darkness and light, these labyrinthine exits and entrances encode the whole of the drama.

As a story therefore of shadows and of enlightenment, of control, and of children, the impress of Bentham can in many ways be complemented by that of Jean-Jacques Rousseau.27 In his Emile or On Education (1762) Rousseau details the individual schooling and instruction of a young boy, and reveals in the process a strong and continuous commitment to the idea of childhood purity. Children are deemed initially free from corruption by virtue of their "special nature." Emerging from the Enlightenment they are the Ideal immanence, and the inhabiters of a lyrical "sleep of reason." It is the experience of, and an exposure to, an adult society which corrupts youth. Left to Nature, Rousseau argued, the child would be a stranger to guilt. With the murder of James Bulger however, the innocence of childhood appears to have come of age. Casting off the romanticism of this infantile purity, Rousseau’s dreamy rationality has been usurped by Goya’s more sinister insight that "the sleep of reason produces monsters!"28 (Jon Venables’ and Bobby Thompson’s crime was headlined "Monstrous") As if heralding the ascendancy of a world borrowed from Golding’s Lord of the Flies, these two ten year olds systematically dismantled a system designed to ensure human safety. Foucault was right, stories of the panopticon are always about power, but in this version it was the power of children not the adult, that was revealed through an architecture.

—————————

"The function of art is to help us find our way back to sources of pleasure that have been rendered inaccessible by the capitulation to the reality-principle which we call education or maturity – in other words, to regain the lost laughter of infancy." Norman O. Brown, Life Against Death29

"There is no doubt," said Superintendent Albert Kirby, "that those two boys were wicked beyond anyone’s expectation . . . they had a high degree of cunning and evil. They could foresee questions to be put to them . . . to be able to do that indicates the level of evil on their part." Of the many things that still haunt his [Kirby’s] team is the "terrible, chilling smile" of Robert Thompson. It happened, said Detective Sergeant Phil Roberts, as the boys were leaving Bootle magistrates after police applied for an extended warrant of detention. Jon Venables was sitting in a car when Thompson walked past towards another vehicle. "Thompson looked at Venables and smiled. It was a terrible, chilling smile. It was a cold smile - an evil smile. I believe the smile said they knew they were responsible . . . and thought they were going to get away with it." Report in The Guardian, Thursday November 25, 1993.

- 1John Major, from an interview with the editor of the Mail on Sunday, Jonathan Holbrow, Sunday, February 21, 1993, p. 8, restated a number of times, during the Bulger trial.

This account of the story of the murder of James Bulger has been written using a number of newspaper sources, including The Guardian, The Times, The Daily Mail, The Daily Mirror, The Observer, The Daily Telegraph, and The New York Times, from Monday, February 15, 1993 – Thursday, December 1, 1993, together with the detailed reconstruction provided by David James Smith, in The Sleep of Reason (London: Century, 1994). - 2J. B Treilhard, Motifs du code d’instruction criminelle (1808), p. 14, from Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish. The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage, 1995) p. 217.

- 3A comparison of the murder statistics of the U.S and of the U.K, as quoted in the The Guardian, Tuesday February 16 1993, seems to support these obvious stereotypes. In Britain the chances of being murdered are 1.3 in 100,000, in the U.S the figure is over 10 per 100,000. In 1991, 607 people were murdered in England and Wales. By contrast in the same year, more than 2000 people were murdered in New York City alone.

The watching of violent television programmes had been explicitly offered as an influential factor upon Jon Venables’ and Bobby Thompson’s behaviour. In his summing up, Justice Morland stated that "I suspect that exposure to violent video films may in part be an explanation.” In particular attention was fixed upon a murder scene in the film, Child’s Play 3, which appeared to contain a number of elements subsequently, thought many people, "re-enacted” in the death of James Bulger. Rupert Murdoch’s Sky Satellite Television had screened the film the same week as the murder. The largely Rupert Murdoch-owned tabloid press, omitted this fact in proposing the burning of every copy of the film. There is no evidence to suggest, however, that either of the two boys had seen the film. See "Indecent Exposure,” article in The Guardian, Friday November 26 1993. - 4Jeremy Bentham, from "Letter I. Idea of the Inspection Principle,” in The Panopticon Writings, ed. Miran Bozovic (London: Verso, 1995) pp. 33–34. The contrived "letter,” as Robin Evans notes, was a common literary device at the time for arranging descriptive or philosophical material for publication. From Robin Evans, "Bentham’s Panopticon. An Incident in the Social History of Architecture,” Architectural Association Quarterly, April/July 1971, p. 21.

- 5Jeremy Bentham, op. cit., p. 1.

- 6Louis-Pierre Baltard, Architectonography of Prisons; or, Parallel of the Different Systems of Planning of Which Prisons are Susceptible, from Peter Collins, Changing Ideals in Modern Architecture, 1750-1950 (London: Faber, 1965) p. 231.

- 7Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish. The Birth of the Prison, p. 205. Louis-Pierre Baltard is quoted by Foucault on p. 319, ft. 13.

- 8Helen Bulger, James’ grandmother, quoted in The New York Times, p. 3.

- 9Kenneth Baker M.P, ibid.

- 10From the Daily Telegraph, March 4, 1993.

- 11Jeremy Bentham, op. cit., p. 95.

- 12From the Daily Telegraph, March 4, 1993.

- 13Jeremy Bentham, op. cit., p. 95.

- 14Unaware of the later challenge they would offer to his system, Bentham, as Robin Evans has pointed out, had ironically regarded children as very appropriate material for his experimentations, since they were at once malleable and in need of physical control - open to the influence of systematic institutionalisation, while also being capable of apparently random acts of mischief or violence. A Nursery Panopticon or Paedotrophium was even described in some unpublished papers of Bentham’s dated 1794. From Robin Evans, op. cit., pp. 33–34.

- 15F. W. J. von Schelling, from Sigmund Freud, "The Uncanny,” trans. James Strachey, in vol. 14 of the Penguin Freud Library, Art and Literature (London: Penguin, 1990) p. 345.

- 16In many ways this "manipulation” raises the somewhat disturbing prospect that one could, literally and figuratively, be "framed” by the video surveillance camera – through enhancement, heads conceivably could be changed, identities altered, whole crimes fabricated.

- 17Walter Benjamin, from "Paris Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” in Reflections. Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott (New York: Schocken Books, 1986) p. 155.

- 18Michel Foucault, op. cit., p. 217.

- 19Jeremy Bentham, Postscript I, of The Panopticon Writings, p. 100.

- 20Ibid., "The Panopticon Letters,” from vol. IV of The Works of Jeremy Bentham, ed. John Bowring (Edinburgh, 1838-1843), p. 45.

- 21Michel Foucault, "Visibility is a trap,” op. cit., p. 200.

- 22Jeremy Armstrong article, headlined, "SICK. Bulger pictures on sale for £2,235 at BT show,” in the Daily Mirror, Wednesday May 25, 1994, p. 6.

- 23Mark Cousins, "Security as Danger,” in Jamie Wagg (ed.), 15:42:32 12/02/93 (London: History Painting Press, 1996) p. 7.

- 24Philippe Ariés, Centuries of Childhood. A Social History of Family Life, trans. Robert Baldick (New York: Vintage, 1962) p. 17.

- 25Ibid., pp. 40–46.

- 26See Frances A. Yates, chapter 3 of The Art of Memory (London: Pimlico, 1966) "The Memory Theatre of Giulio Camillo,” pp. 135–162.

- 27The similarity of the "projects” of Bentham and of Rousseau is also detailed by Foucault. In his conversational essay, "The Eye of Power,” he notes that ‘Bentham was the complement to Rousseau. What in fact was the Rousseauist dream that motivated many of the revolutionaries? It was the dream of a transparent society, visible and legible in each of its parts, the dream of there no longer existing any zones of darkness, zones established by the priveleges of royal power or the prerogatives of some corporation, zones of disorder.” From Michel Foucault, Power/Knowledge. Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977, trans. Colin Gordon, Leo Marshall, John Mepham, and Kate Soper (New York: Pantheon, 1980) p. 152.

- 28Quoted by Alison James and Chris Jenks, "Public perceptions of childhood criminality,” in The British Journal of Sociology, vol. 47, no. 2, June 1996, p. 31.

- 29Norman O. Brown, Life Against Death. The Psychoanalytical Meaning of History (Wesleyan University Press, 1985) p. 60.