No 1: Das Kino bebt

No 1: Das Kino bebt

[english version below]

Das Beben beschreibt sowohl geologisch-tektonische Spannungsentladungen, wie auch spezifische Gefühlsbereiche des Menschen. Im Kino ist das Beben immer mit Spannungs- und Erregungszuständen verknüpft. Seit seiner Erfindung scheint sich das Filmbild, das auf einem Flickereffekt beruht, nicht nur aus Vibrationen zu generieren. Seine vielleicht wesentlichste Qualität besteht darin, die unterschiedlichen Gefühlsregister, Angst, Trauer, Freude, erotische Spannung bis auf ihre Höhepunkte zu treiben. Die Filmgeschichte ist reich an Spannungs-Episoden. Schon ein Kurzfilm der Brüder Lumière (Arrivée d'un train à la Ciotat, 1896) trieb die Spannung über das Maß hinaus, so daß einige Menschen fluchtartig den Saal verließen. Feinere Erregungszustände können über visuelle und akustische Lektüren im Innern der Zuschauer evoziert werden, wie z.B. in Viscontis La Terra Trema (1947/48), der das Beben zusätzlich im Titel führt.

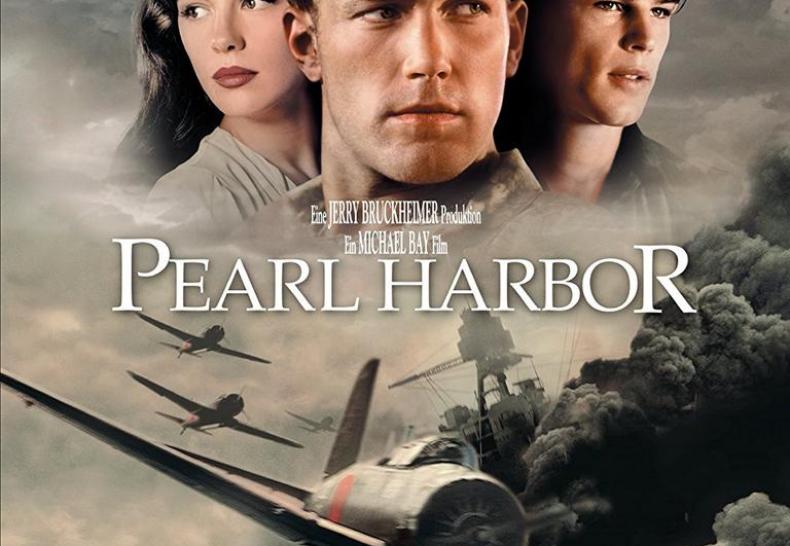

In Katastrophenfilmen kann man das Beben über die Bild- und Toneinwirkungen körperlich erfahren. Mit großem Aufwand imitiert dieses Filmgenre seit den 70er Jahren Flugzeugabstürze, Feuersbrünste, Erdbeben, Flutwellen und Wirbelstürme. Die Erschütterungen der Soundtechnologie (Sensurround) stehen den Auswirkungen eines Erdbebens seither kaum nach. Beim Filmereignis Earthquake (1974, dt. Erdbeben) erbebte nicht nur die Zuschauerschaft, sondern auch die Seismographen einiger Erdbebenwarten. Die Erregungsmetaphern der Presse überschlugen sich. Im belgischen Ostende mußte der Film sogar verboten und ein Kino geschlossen werden, weil einige ältere Häuser durch das Kinobeben vom Einsturz bedroht waren. Neben diesen handfesten Erschütterungen verzeichnen die 70er Jahre auch geistige Erdrütsche in der Filmtheorie. Mit der Publikation von Langage et Cinéma (Metz 1971) etablieren sich der 'Film als Text' und die 'kinematografische Schreibweise'. Sie lösen eine internationale Flut textueller Filmanalysen aus. In diesem Kontext wird ein Pamphlet zum Markstein feministischer Filmtheorie (Mulvey 1973) und ein Essay thematisiert zum erstenmal die Dimension des Zuschauers "Beim Verlassen des Kinos" (Barthes 1975).

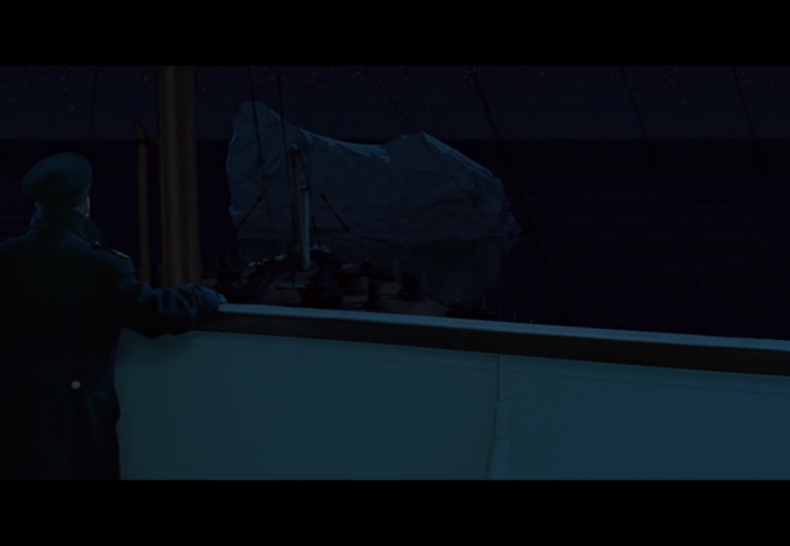

In den 90er Jahren gibt es erneut ein Kinobeben. Die erste Ausgabe von 'nach dem Film' setzt sich mit den Facetten dieses aktuellen Bebens auseinander. Sie beschäftigt sich mit den neuen Katastrophenfilmen (Armageddon, Titanic, Twister u.a.) und dem Erzittern der Zuschauerschaft (Scream). Die technischen Erschütterungen betreffen jetzt nicht mehr nur Bild und Ton in ihrer Wirkmächtigkeit, sondern die gesamte Filmproduktion und -distribution. Mit dem Siegeszug digitaler Technologie wird auch die Frage nach dem elektronischen Erinnerungsvermögen des (ehemals fotografischen) Mediums neu aufgeworfen. Das Kinobeben begleitet aber nicht nur die technischen und ökonomischen Globalisierungsschübe, es 'erzählt' auch von den psychischen und kulturellen (De-) Formationen in dem ihm eigenen Visual Discourse. Die Filmtheorie der 90er Jahre wendet sich flankierend einem neuen Paradigma zu, das jenes vom 'Film als Text' ersetzt und das Kinematografische als ein 'Ereignis' in sein Zentrum rückt.

'nach dem Film' lädt ein zum Weiter-Schreiben und wünscht allen Leser/innen viel Vergnügen. Herzlichen Dank an diejenigen, die das Entstehen der ersten Ausgabe unterstützt haben.

Für die Redaktion Winfried Pauleit

No 1: The Tremors of the Cinema

Editorial

The word tremor conjures up not only geological tectonic releases of tension, but also specific areas of human emotion. In the cinema, tremors are always tied to states of tension and excitement. Ever since its invention, the filmic image, which is based on a strobe effect, seems not only to have been generated by vibrations. Perhaps its most essential quality lies in pushing the various registers of emotion – fear, mourning, joy, erotic tension – to a climax. Film history is rich in episodes of tension. A short film by the Lumière Brothers (Arrivée d'un train à la Ciotat, 1896) pushed that tension so far, that some of the spectators fled from the site of exhibition. More refined states of tension can be evoked in the interior of the spectator by visual and acoustic readings, as for example in Visconti's La Terra Trema (1947/48), which also includes tremors in its title.

In catastrophe films, tremors can be experienced in the body through visual and sound effects. Since the 1970s, this film genre has imitated plane crashes, fire storms, earthquakes, tidal waves and tornadoes. The jolts of sound technology (Sensurround) have since come to almost approach the effects of an earthquake. At the film-event Earthquake (1974), not only did the spectators, but also the seismographs experienced the earthquake. The metaphors of excitement in the press took on a fevered pitch. In the Belgian town Ostende the film had to be forbidden and one movie theater was closed, because some older houses were threatened with collapse by the shaking of the theater. Besides these palpable jolts, the 70s can also be characterized by plate shifts in film theory. With the publication of Langage et Cinéma (Metz, 1971), 'film as text' and 'cinematic écriture' became established as ways of looking at film. They released an international flood of textual film analyses. In this context, one pamphlet becomes a milestone of feminist film theory (Mulvey 1973) and another essay thematized the dimension of spectatorship for the first time: "Upon Leaving the Movie Theater" (Barthes 1975).

In the 90s, the tremors of the cinema have returned. The first issue of 'nach dem film' confronts the many facets of these current tremors. It looks as the new catastrophe films (Armageddon, Titanic, Twister, etc.) and the shaking in the spectator (Scream). The technical jolts not only apply to image and sound in their effective power, but also the entire apparatus of film production and distribution. With the victory of digital technology, the question of the electronic memory capacity of the formerly photographic medium is newly posed. The tremors of the cinema are accompanied not only by the technical and economic shifts of globalization; they also tell of the psychic and cultural (de)formations in their own visual discourse. The film theory of the 90s turns towards a new paradigm, which replaces 'film as text' with the cinematographic as 'event' at its center.

'nach dem film' invites a continuing exchange, and hopes that all its readers enjoy this first issue. Many thanks to those who supported the work on the first issue.

For the editors Winfried Pauleit

(Translated by Brian Currid)