Expended Cinema

Expended Cinema

Curating Cinema’s Futures in an Era of Transition

In 1996, during a brief moment of reflection following cinema’s first centenary and in the face of an increasingly digital dominated media landscape and a perceivable fracture between cinema and film, cinema’s future seemed anything but assured. This future seemed to exist now in a simultaneous state of over-determination and heightened precarity. This was also an era in which cinema was more likely than ever before to find its way into the spaces of the visual arts, the gallery and the museum. During this period a number of large-scale exhibitions were held that would mark this centenary including “Hall of Mirrors: Art and Film since 1945” (Museum of Contemporary Art, MOCA, Los Angeles, 1996). Under the influence of head curator Kerry Brougher and with funding from corporate behemoths like Time Warner and Fox Entertainment, this ambitious exhibition would take a retrospective glance at the relationship between art and film, bringing its visitors up to date on this complex dynamic as cinema’s first century drew to a close. What then can an exhibition like “Hall of Mirrors” reveal to us of cinema’s futures?

Upon entering the exhibition visitors were met by a dizzying array of works and media, from photographs (Wegee’s images of cinema audiences in the 40s, Hiroshi Sugimoto’s long exposures of cinemas and drive-ins, Cindy Bernard’s revisitings of familiar film locations photographed long after the point they had become unrecognizable), paintings (Salvador Dali’s backdrop to a dream sequence in Hitchcock’s SPELLBOUND (1945), Edward Hopper’s New York Movie (1939), Edward Ruscha’s Exit (1990)), and a range of other sculptural assemblages and installation works (Joseph Cornell’s boxes, Fabio Mauri’s Senza (Without, 1976) Helio Oiticica and Neville D’Almeida’s QUASI-CINEMA (1973)). All told the exhibition would feature work by over 80 artists and filmmakers, with upwards of 200 individual works in total. What visitors were less likely to encounter there was the projected moving-image. Although this was not without exception references to cinema’s more familiar histories mostly took the shape of short citations, easily digestible excerpts screened on the many monitors interspersed throughout the exhibition. The majority of those extracts were drawn from recognizable forms of narrative cinema – Ridley Scott’s BLADE RUNNER (1982), Michael Powell’s PEEPING TOM (1959), Hitchcock’s PSYCHO (1960).

While “Hall of Mirrors’s” purview was primarily historical, offering an extended history of the relationship between art and film since the end of the Second World War, the exhibition practices on display here would also make visible the beginnings of a so-called cinematic turn, a shift within the visual arts that was at the time only beginning to take hold.1 The exhibition reveals a number of tensions that will be made visible in this turn and recent engagements with cinema on behalf of the visual arts. There is an initial suggestion here of a fracture between what is referred to in the exhibition catalogue as the more “reductivist” tendencies of a modernist avant-garde and the more “expansive” possibility of an engagement with cinema rooted in the “deconstruction” of its fundamental components. In the first category, the category of an avant-garde and experimental cinema, this was a mode of practice which had to date been primarily articulated through contexts in which cinema’s so-called Black Box conditions had remained more or less intact. In practice this would mean that these operations were rarely compatible with the traditional White Cube conditions of the gallery/museum. In a discussion about the role of the projected image in contemporary art the curator Chrissie Iles describes how an avant-garde cinema will “insist that you come, quite rightly, and sit in the space and watch their films from beginning to end”—practices which were actually quite “antithetical to the art world” (Iles 2003: 94).

The incorporation of cinema into “Hall of Mirrors” would do little to interrupt or disrupt existing conditions and exhibition practices, the White Cube remained relatively intact here in spite of cinema’s presence. For Peter Lunenfeld, the exhibition’s inadequacies in this regard were symptomatic of a wider tendency within the visual arts, an “inability to grapple with the spatial, aural, and temporal qualities inherent to cinema” (Lunenfeld 1996). What visitors to the exhibition encounter here more often than not were works that took as their starting point a consideration of cinema, but rarely would they encounter cinema itself. The cinema discovered here was a cinema articulated through other means.

Several years later, and with the cinematic turn now in full swing, the exhibition “Beyond Cinema: The Art of Projection: Films, Videos and Installations from 1963 to 2005” (Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, 2006), was a more concerted attempt to better incorporate cinema’s Black Box conditions into the space of the gallery/museum. In contrast to “Hall of Mirrors,” “Beyond Cinema” made a considerable gesture toward accommodating itself to cinema and the exhibition suggests a hybrid space somewhere between both these sets of environmental conditions. The exhibition would also rely more heavily on film materials, most frequently in the form of 16mm projection. Curated by Stan Douglas and Christopher Eamon, “Beyond Cinema” incorporated works by a number of artists who would help define the term „cinematic turn“ and its influence. Alongside work by Douglas (whose installation piece Overture (1986) also featured in “Hall of Mirrors”) the exhibition featured other key works that had helped describe the central tendencies of this turn. Included here was Douglas Gordon’s highly influential 24 Hour Psycho (1993), Monica Bonvicini’s double projection found-footage work Destroy She Said (1998; a work which drew on existing iconic performances by the likes of Catherine Deneuve, Monica Vitti and Shelley Winters), and L’Ellipse (1998), a three-channel work by Pierre Huyghe, a variation on Wim Wenders’ 1977 film THE AMERICAN FRIEND. The exhibition also suggested a possible lineage for these practices, proposing the Expanded Cinema movement of the 1960s and 1970s as the key precursor to this recent cinematic turn. “Beyond Cinema” featured also several iconic works in this regard including Anthony McCall’s Line Describing a Cone (1973), Dan Graham’s Body Press (1970–72), and VALIE EXPORT’s Adjungierte Dislokationen (1973).

A foreword to “Beyond Cinema” typifies a tendency within the visual arts to interrogate cinema primarily in relationship to its spatial rather than temporal dimensions:

“Film and video within the art context have discovered the dimension of space: in exhibitions, large-format moving-images can be found on walls, the ceiling or floor: multiple projections appear simultaneously on several screens or as performances in specially designed architectures and installations that visitors can enter and move about in” (Eamon et al. 2006: 11).

“Beyond Cinema” pointed to the Expanded Cinema movement of the 1960s and 1970s as the most logical precursor for these kinds of hybrid exhibition practices, which now involved darkened rooms and a projected image (a move away from the monitor-based exhibition practices of “Hall of Mirrors”).

VALIE EXPORT’s Adjungierte Dislokationen is screened here as a three-channel installation piece. EXPORT is a key figure in terms of the legacy of Expanded Cinema, and in making this work EXPORT strapped an 8mm camera to her chest, another to her back, while a third camera (16mm) filmed her moving through public spaces. Through this multiscreen, multi-format projection (one 16mm and two 8mm projections) we can observe each iteration of EXPORT’s actions playing out simultaneously. EXPORT’s cinema would reinsert the body, drawing attention to the physical space and forcing the audience to shift from its previously fixed position. In elaborating on this legacy EXPORT describes how “[i]n Expanded Cinema, the system of the cinema [dispositif] was taken apart in single pieces, deconstructed, destroyed” (Breitwieser 1996: 119). As per this logic cinema is situated by “Beyond Cinema” and its curators as a limit that could be transcended through art. The notes to “Beyond Cinema” describe how its exhibition practices “[dispense] with static seating, [do] not dictate any one kind of fixed line of vision, and [have] long since jettisoned the linear narrative”2 echoing the rhetoric that supported Expanded Cinema in its initial iterations, an influence that can be seen also in the exhibition’s insistence upon multiscreen works and a non-static spectator position. Other examples of split and double screen projection reoccur throughout this exhibition in work by Pipilotti Rist, Monica Bonvicini, Eija-Liisa Ahtila, Pierre Huyghe, and John Massey.

Chrissie Iles suggests that the kind of hybrid spaces we encounter in exhibitions like “Beyond Cinema” offer a necessary corrective to the ways in which the spectator has been situated by cinema in its more familiar formations. The existing model is disrupted and broken apart here by being folding into the White Cube of the gallery/museum. In contrast to cinema’s existing ideological effects in which there is “no circulation, no movement, no exchange” the existing “model is broken apart” by the hybrid spaces of exhibitions like “Beyond Cinema” (cf. Iles 2001: 33). In contrast to a classical cinema dispositif

“the darkened gallery’s space invites participation, movement, the sharing of multiple viewpoints, the dismantling of the single frontal screen, and an analytical, distanced form of viewing. The spectator’s attention turns from the illusionism on the screen to the surrounding space, and to the physical mechanisms and properties of the moving-image: the projector beam as a sculptural form, the transparency and illusionism of the cinema screen” (ibid.).

The strategies of Expanded Cinema frequently evoke a more universalized understanding of how cinema spectatorship functions, a tendency reiterated by “Beyond Cinema” which “seeks to reflect on and consider the prerequisite conditions of the filmic, to test the effect they have in space and investigate ways of questioning habitual patterns of perception” (Eamon et al. 2006: 11).

“In contrast to the hypnosis induced by the pitch-blackness of the cinema, within which the single bright screen seizes our minds in its distracting grip, the dimly lit gallery engages the viewer in a wakeful state of perception” (Iles 2001: 34).

Chrissie Iles situates cinema’s ideological effects in relation to its environmental conditions, and by doing so re-enacts some of the more reductive tendencies of an Expanded Cinema which radically reduced the primacy of the text and what it was that actually appeared on screen. Iles describes this as a “postminimalist decentering of the viewing subject” and in doing so she suggests that the “dismantling” of an ideological machine would be coincident with the dismantling of the actual machine and its viewing conditions. Olga Bryukhovetska acknowledges some of the more apparent limitations of this mode of thinking: “[t]o reduce the positioning performed by the cinematic dispositif to the physical position of the viewer is the same empiricist fallacy as to identify the subject with the chair he or she occupies” (Bryukhovetska 2010).

As cinema continued its transition from an analogue to a digital realm, this would become something of a renaissance period for Expanded Cinema and the theories that had both helped inspire it or were historically coincident with its emergence. This tendency demonstrated also by other major retrospectives including “X-Screen: Film Installation and Actions of the ‘60s and ‘70s” (MUMOK, Vienna, 2003–04) and a conference on the topic of Expanded Cinema held at Tate in 2007—”Expanded Cinema: Activating the Space of Reception” (as well as a retrospective held at BFI Southbank a year later—“Expanded Cinema – The Live Record”). At each point of return, including more contemporary iterations which reenact gestures from that movement, this seems to suggest also an additional point of return and an understanding of cinema spectatorship that was also first drawn out in the 1960s and 1970s, demonstrated through the work of influential theorists like Jean-Louis Baudry and Marcelin Pleynet.3 In his introduction to the exhibition “X-Screen: Film Installations and Actions in the 1960s and 1970s”, Matthias Michalka refers to these debates and their continued influence. Again the focus here is on how the spectator is situated ideologically by cinema:

“The operation of filmic illusionism and the production of consciousness-forming cinematographic effects result from an unlimited dominance of the eye, a complete negation of the body, fixed in place, the denial of the actual physical space, and the intended concealment of the material and technological foundation of the light-image projection. The ideological apparatus imperceptibly assigns the spectator his or her place in the cinema, locating him or her in the filmic event and thus positioning him or her as a subject” (Michalka 2004: 8).

The Expanded Cinema was typically seen in contrast to be disrupting and challenging this mode by interrupting some or other aspect of its arrangement. Work created by the artists associated with the Expanded Cinema movement would alternately disrupt, disembody or radically reconstruct the cinema’s “primordial dimensions,” all of that which would together account for a more recognizable dispositif of cinema. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s the artists and filmmakers associated with this movement were also among the first to begin to introduce a cinema which could incorporate multiple screens, live performances, and an imageless or even projector-less configuration.

In “Hall of Mirrors,” the presence of cinema did little to interrupt or upset the existing White Cube conditions of the gallery and museum while “Beyond Cinema” attempted to amalgamate in its exhibition strategies the White Cube and the Black Box. Jeffrey Shaw and Peter Weibel’s exhibition “Future Cinema: The Cinematic Imaginary After Film” (ZKM, Karlsruhe, 2002) was something else entirely, leaving behind both these contexts in favor of a very different future. “Future Cinema’s” exhibition strategies would place their emphasis “on installations that diverge from the conventional screening formats, and explore more immersive and technologically innovative environments such as multiscreen, panoramic, dome-projection, shared multi-user, and on-line configurations” (Shaw 2003: 21). “Future Cinema” would also purposefully extend and refer to the legacy of an Expanded Cinema not least through the exhibition’s centerpiece—a work by Jeffrey Shaw, a dome-shaped screen environment in which audiences are enveloped by a “stream” of images, which effectively re-imagined Stan Vanderbeek’s “Movie Drome” for the digital age.

For Weibel and Shaw, this “Future Cinema” represented the final stage in cinema’s transformation— the first stage was the Expanded Cinema movement of the 1960s, the second, the “video revolution,” begun in the 1970s, and finally now with the emergence of the “digital apparatus” a future cinema. Weibel and Shaw treat the original terms of Expanded Cinema with some specificity here, and Gene Youngblood, one of the movement’s more influential figures, would even contribute an essay to the exhibition’s publication. In the teleology described here the first phase, Expanded Cinema, “extended the cinematographic code,” while the second phase, the arrival of video, “allowed intensive manipulation and artificial construction of the image in a postproduction stage” and finally the emergence of a digital apparatus in all of its utopian possibility, “created an explosion of the algorithmic image” enabling “completely new features like observer dependency, interactivity, virtuality, programmed behavior” (Weibel 2003: 16).

The trajectory described by Weibel and Shaw is a transparently teleological and utopian vision in which it is technology itself, rather than any particular human or artistic intervention, that would drive the shape of cinema’s future. In Weibel and Shaw’s understanding, a “digital revolution” in which “artists” were replaced by “experts”, would bring with it the rise of a digital singularity, absorbing and improving upon the potentials of previously existing media, a change that will now allow for a “more radical and heterogeneous future for the cinema” (Shaw 2003: 26).

Weibel’s position here echoes that of Lev Manovich, who, in essays like “What is Digital Cinema?” (1996), similarly outlined a media history in which cinema was reduced to little more than a stepping stone in the development of more advanced media technologies and new aesthetic possibilities:

“Cinema, which was the key method to represent the world throughout the twentieth century, is destined to be replaced by digital media: the numeric, the computable, the simulated. This was the historical role played by cinema: to prepare us to live comfortably in the world of two-dimensional moving simulations. Having played this role well, cinema exits the stage. Enters the computer” (Manovich 1996, reprinted 2005: 30).4

In his article ”New Media from Borges to HTML” (2003), largely written in response to the kind of exhibition practices that typify “Future Cinema,” Manovich would make the claim that “the greatest avant-garde film is software such as Final Cut Pro and After Effects” (Manovich 2003: 15). This reification of technology and software (over and above any of the uses to which technology and software might be put), helps typify the position of Manovich and “Future Cinema” as a whole.

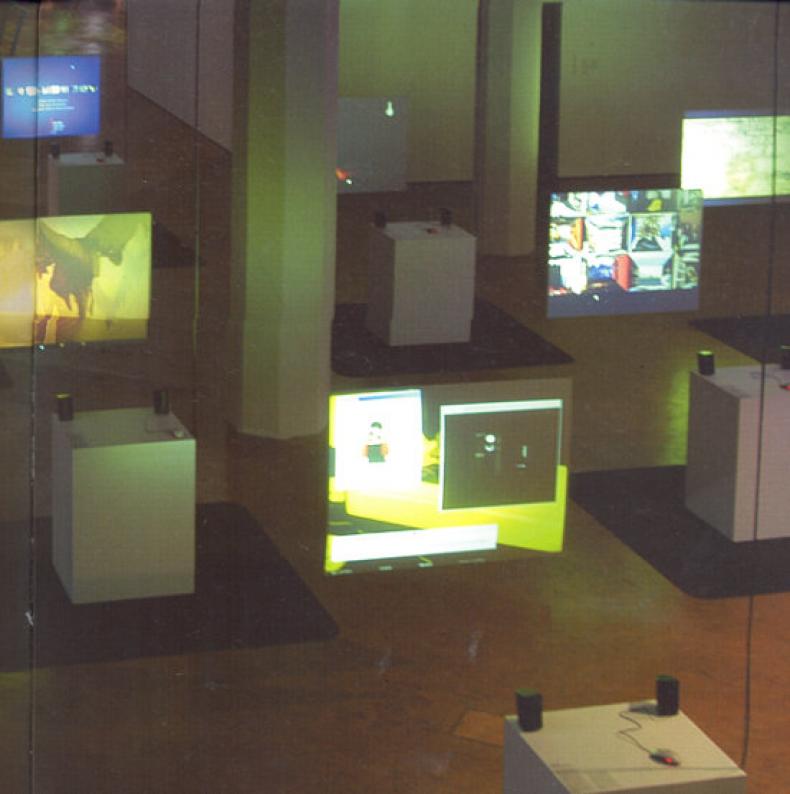

This exhibition supports an impression of self-imposed exclusion, taking place not in the recognizable White Cube space of the gallery/museum but also not attempting to recreate in any way the Black Box conditions of cinema. The large atrium space of the ZKM, where the exhibition took place, evoked instead the corporate environments of tech start-ups, open-plan offices, and software developers, with strip lighting overhead, desktop monitors scattered throughout, visible desktop computers and hard drives, and a seemingly fetishistic presence of knotted cables, blinking lights, and computer hum. Non-permanent dividers separated this open-plan space into viewing cubicles and as a result the utopian environment most clearly suggested by “Future Cinema” was not the cinema or the gallery/museum but the spaces of Silicon Valley, “innovation academies,” and the imaginary utopias of “campus” corporations like Google and Facebook. While “Future Cinema” was prophetic in its vision of the corporatization of art, it had little if anything to do with cinema or its futures.

As different as each of these exhibitions were, they represented during this period some of the various poles of possibility contained in cinema’s future. In “Hall of Mirrors” and “Beyond Cinema” the “death of cinema” is already a given. As Jean-Christophe Royoux notes in his catalogue to a similarly framed exhibition “Cinéma Cinéma” (Eindhoven, 1999),

“[t]his is the basis of the contemporary artist’s relation to film: the sense of an inevitable post-cinematic era, of an end of sorts, which implies a transferal and a necessary transformation of its modes of representation.” (Royoux 1999: 21)

An exhibition like “Future Cinema” would on the surface, and in line with Lev Manovich’s thinking on the subject, suggest a more open realm of possibility in terms of cinema’s future but there was little here that remained recognizable as cinema.

The twin poles of possibility presented here are death or transcendence. As a means to understand the wider possibilities of cinema in the digital age “Hall of Mirrors,” “Beyond Cinema” and “Future Cinema” place a limit on the kinds of future we can imagine. Where then can we locate an alternative?

When considering the continued influence of the Expanded Cinema movement, we can look back to Peter Kubelka’s Invisible Cinema project which once offered something of a corrective to those positions, fixing in place those same aspects the Expanded Cinema sought to disrupt. The Invisible Cinema suggests a true polarity to the gallery’s White Cube, a cinema space in which every surface is painted matt black and barriers separate individual spectators from each other, allowing for a more complete immersion in an analogue, projected, cinema image.

This was a more complete consolidation of cinema’s black box conditions and this is the image of cinema that has been maintained at the Austrian Film Museum. Yet, in Kubelka's view this was not a cinema that would become static or calcified. In the same year the exhibition “Hall of Mirrors” was unveiled, Peter Kubelka also created and curated his film cycle retrospective “Was ist Film” for the Film Museum. This program was a response to cinema’s increasingly precarious position at the close of the last century and the cycle consisted of 150 individual films and featured work by over 50 filmmakers from the early moving image experiments of W.K.L. Dickson and the Lumières to Paul Sharits’s structuralist investigations of the 1960s. The program, created to mark the cinema’s centenary, elucidated Kubelka’s specific understanding of cinema as an “unfinished project” and “a tool which cultivates new ways of thinking”.5 The project premised on Kubelka’s understanding of cinema’s role as both “artifact and event”. Where once this had been a straightforward definition of cinema that could acknowledge its material and immaterial aspects (cinema as a technologically driven medium and our spatio-temporal experiences of the same), by the end of the century this understanding would seem like a provocation in the face of a cinema that had grown increasingly amorphous in its limits and in which the prospect of artefact and event is almost always treated as an either-or proposition.

A project like “Was ist Film?” reminds us also that the spaces of the visual arts are not the sole sites through which issues around curatorship and cinema have been articulated. These issues can also be considered in relation to what Alexander Horwath refers to as the “the normal case of cinema”.6 Kubelka’s program was a history of cinema but it was also designed to initiate possible continuations of the cinema project as he saw it, to motivate continued productive engagement with cinema’s histories to date (the pluralization of cinema’s histories is an essential gesture here). The project revealed important points of both continuity and rupture between the cinema of our media technological present and the cinema of the past. The program was also highly idiosyncratic, an anticanonical project that rewrote cinema history in Kubelka’s terms, and a project that would demand equally impassioned curatorial and canonical responses in turn.7 Just as Kubelka’s films are often considered “film theory in practice”, this can be extended to a curatorial project which was also, very much, a theory of cinema.

At the center point of Kubelka‘s project was Vertov’s THE MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA (1929), an essay in contingency which has been as essential within accounts of avant-garde traditions as it has been within the histories of documentary film. Vertov’s film announced in 1929 a wide spectrum of aesthetic and formal possibilities for cinema. Many of the futures Vertov’s cinema promised remain largely uninhabited and the film highlights the contingencies and plurality at the heart of Kubelka’s project, and arguably the project of cinema generally. What Kubelka demonstrates in this is that any shape cinema has taken was in no way predetermined, cinema has been shaped and molded by a variety of forces, technological, creative, social, and while Kubelka’s project suggests an essentialist project (what film is), it was also a pluralist response, it demands that in writing a history of cinema we acknowledge that this history is never static, that it is constantly made available for reinvention and that cinema’s future in turn is not yet determined but open to negotiation. Kubelka reminds us that in considering cinema’s future we must acknowledge not only what cinema is but also all of what it might have been and could yet be, all of cinema’s contingent possibilities including its projected futures which have not yet come to pass.

- 1While it is hard to trace when precisely this term begins to take hold as a popular signifier for the visual arts’ turn not only toward the projected moving-image but also to a broader understanding and appreciation of the cinematic arts in general some key texts which have looked at this era and its influence include Erika Balsom (2013) and Maeve Connolly (2009), Although a little more general in its outlook Tanya Leighton’s (2008) edited collection is also essential.

- 2Catalogue notes from the exhibition “Beyond Cinema: The Art of the Projection. Films, Videos and Installations from 1963 to 2005”.

- 3Pleynet- “the cinematographic apparatus is a properly ideological apparatus, it is an apparatus that disseminates bourgeois ideology before disseminating anything else. Before it produces a film, the technical construction of the camera produces bourgeois ideology.” In “économique, idéologique, formel,” Cinéthique. no.3, (1969): 10.

- 4“Future Cinema” also included a work by Manovich, a projection installation titled Soft Cinema(2002) in which spectators recline on specially designed chairs to experience Manovich’s variation of a “database cinema.”

- 5This description is taken from program notes on the Austrian Film Museum’s website (2016). The filmcycle continues to play at the musuem at the rate of one program per week. Once the cycle has reached its conclusion it begins again.

- 6These notes are taken from program notes by Horwath prepared for his film program at documenta 12. He goes on, “film at documenta 12 is not an object to be taken home or a path to be sauntered along, but a spatially and temporally defined act of contemplation and exchange with the world.“

- 7I am thinking in particular here of Alexander Horwath’s ongoing project at the Film Museum “Utopia of Film.”

Austrian Film Museum (2016): What Is Film: Program 23–27, in: Österreichisches Filmmuseum Wien, http://www.filmmuseum.at/jart/prj3/filmmuseum/main.jart?rel=en&content-id=1219068743272&schienen_id=1238713598995&reserve-mode=active&ss1=y (22.11.2016).

Balsom, Erika (2013): Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Breitwieser, Sabine (1996): White Cube/Black Box: Video Installation Film, Wien: EA-General Foundation.

Bryukhovetska, Olga (2010): ‘Dispositif’ Theory. Returning to the Movie Theater, in: ART-iT 10, http://www.art-it.asia/u/admin_ed_columns_e/apskOCMPV5ZwoJrGnvxf (22.11.2016).

Connolly, Maeve (2009): The Place of Artists’ Cinema. Space, Side, and Screen, Bristol/Chicago: Intellect Books.

Eamon, Christopher et al. (2006): Zur Ausstellung, in: Jäger, Joachim et al., eds.: Beyond Cinema: The Art of Projection. Films, Videos and Installations from 1963 to 2005, Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 10–13.

Iles, Chrissie (2003): Round Table. The Projected Image in Contemporary Art, in: October 104: 71–96.

Iles, Chrissie (2001): Into the Light. The Projected Image in American Art, 1964–1977, New York: Whitney Museum of American Art Books.

Leighton, Tanya, ed. (2008): Art and the Moving Image, London: TATE Publishing.

Lunenfeld, Peter (1996): Hall of Mirrors. Art and Film since 1945, Art Forum 34:10, available at https://www.questia.com/magazine/1G1-18533856/hall-of-mirrors-art-and-film-since-1945

Manovich, Lev (2003): New Media from Borges to HTML, in: Wardrip-Fruin, Noah/Montfort, Nick, eds.: The New Media Reader, Cambridge, MA/London: MIT Press, 13–28.

Manovich, Lev (1996): Cinema and Digital Media. Reprinted in Andrew Utterson, ed. (2005) Technology and Culture: The Film Reader, New York: Routledge, 27-30.

Michalka, Matthias, ed. (2004): X-Screen. Film Installations and Actions in the 1960s and 1970s, Cologne: Walther König.

Pleynet, Marcelin (1969): Économique, idéologique, formel, in: Cinéthique 3, 7–14.

Royoux, Jean-Christophe (1999), “Remaking Cinema”, in Bloemheuvel, Marente and Guldemond, Jaap, ed., Cinéma Cinéma. Contemporary Art and the Cinematic Experience (Eindhoven: Stedelijk van Abbemuseum, S. 21-27.

Shaw, Jeffrey (2003): Introduction, in: Shaw, Jeffrey/Weibel, Peter, eds.: Future Cinema. The Cinematic Imaginary after Film, Cambridge, MA./London: MIT Press, 19–29.

Weibel, Peter (2003): Preface, in: Shaw, Jeffrey/Weibel, Peter, eds.: Future Cinema. The Cinematic Izxmaginary after Film, Cambridge, MA./London: MIT Press, 16–18.