The Consulted Cinema and Some of Its Effects

The Consulted Cinema and Some of Its Effects

I wish to name the films we can see on the internet the ‘consulted cinema,’ so as to discriminate the ‘cinema’ and the various reproductions of films. What are the effects of the ‘culture of consultation,’ referring to the films available on the internet, as opposed to and articulated by the ‘reference prints,’ referring to the culture of seeing films on the cinema screen? Which effects are generated by such a ‘culture of consultation’—effects on Cinephilia as well as on new styles—for the best and for the worst? Which relationships can we observe so far between the ‘consulted cinema’ and the films directly made with digital tools according to contemporary practices of immediate diffusion? I will suggest three new gestures, so that film archives can become a main site not only of preservation, restoration and diffusion, but also of cultural emancipation.

With this contribution, I want to offer you the most optimistic vision of the future of film—not because of my capacities for denial, but thanks to a great range of objective facts. I wish to show that one of our possible futures not only avoids the disappearance of film (as material), but leads to a multiplication of its forms of appearance.

The film industry produces objects, but mainly it produces assumptions. Whenever it forces us to use the latest tools, to adopt new formats and to follow new standards, some filmmakers, videographers and artists are rebelling and practice forms of technical disobedience which becomes an aesthetic movement in itself. The contemporary technical disobedience crosses at least two traditions: the tradition of Lettrism (practicing low tech and, with the ‘infinitesimal film,’ inventing no tech at all) and Michael Snow’s LA RÉGION CENTRALE (1970) — for which we have to invent the term single tech: not only is the work itself a single machine, but it also represents a single use of the machine, which breaks the protocols and postulates a discipline all by itself.

Today, the opposers are refusing technological guidelines in manifold ways: by inventing their own tools, by reviving old instruments, by diverting circuits and instructions. Throughout the history of cinema, artists have not only created their own fleet, but also their own logic and their own technical temporality. Melancholic, a-synchronous or simply in advance of all others, they allow us to locate and criticize the industrial requirement. Speaking about analogue film, let us face some positive facts:

- All over the world, independent laboratories are maintaining film and keeping it alive. Let us mention, among others: Studio Een (Rotterdam, 1990), L’Atelier MTK – Métamkine Group (Grenoble, 1992), L’Abominable (Paris, 1996), L’Etna (Paris, 1997), Double négatif (Montreal, since 2004), Film-Koop in Vienna (since 2008), Zebre Lab (Geneva, 1996), Worm Filmwerkplaats (Rotterdam). 1

- Outside of these independent Labs, major films and even masterpieces are still being produced in S8 and 16mm. Let us mention, among many interesting creations, three recent masterpieces, which will remain as landmarks in the history of film art while the foam of average digital products will have vanished: NATPWE, FEAST OF THE SPIRITS, Tiane Doan Na Champassak / Jean Dubrel, France/Myanmar, 2004–13, 30 min, shot in 16mm and S8; DITHRYAMBE TO DIONYSOS, Béatrice Kordon, France, 2007, 56 min, shot in S8; JAJOUKA, QUELQUE CHOSE DE BON VIENT VERS TOI (Something Good Comes to You), Etant donnés (Eric/Marc Hurtado), 2012, Morocco/France, 64 min, shot in Super 16mm.

- A positive recent sign is the release of the Logmar camera announced by the Denmark-based Logmar company: “The First 8mm Camera Made in over 30 Years Will Be Released in December:” a 8mm camera with digital viewfinder, Wi-Fi and audio recording capabilities while still using Kodak Film (see Renée 2014).

Just looking at these three developments, what remains is not only a great quality of analogue movies, but also the potential for fascinating new developments. This energy of persistence co-exists with the exponential multiplication of degraded reproductions of films. I will now evoke three cases of fertile confrontations between gorgeous analogue film and its sometimes fascinating degraded versions.

- The benefits of consultation versions;

- The invention of film as a model: new modes of film visibility;

- The case of a luxurious version: and more tasks for the film archives.

1) The benefits (or virtues) of consultation versions

A minimal mission for any scholarly work on film is to articulate and create awareness for the fact that—in most cases—films seen on the internet are ‘versions for consultation,’ ‘consultation films,’ resulting from various processes of degradation. Instead of complaining about this degradation, however, we can observe constructive and positive aspects of the immediate availability of movies.

A. The first aspect relates to the diversity of the ‘Act of Seeing:’ Thanks to these ‘degraded versions,’ we can engage more fully with Jean-Luc Godard’s famous formula concerning “all the films which have not been seen.” Godard, of course, was referring to the films that have not been understood. But today, we must also consider another meaning: namely, that the supreme ‘Act of Seeing,’ in a Brakhagian or Godardian sense, is only one practice among many others which are more profane or even unholy. We can simply consult, check, or just use a film. And maybe such a versatility and stratigraphy of our apprehensive relationship to film, extensive throughout the screening and intensive in its simultaneity, has always existed, except that the ritual of projection was hiding it. So the uses of these consultation versions can help us to clarify or expose the diversity of film perception.

B. A second benefit of the availability of consultation versions concerns the traditional use of images as data for counter-information, and film as a proof or counter-proof.

A historical example of an alliance between the celluloid print and the degraded digital version of a film is SARKOLONISATION, a 2009 short agit-prop essay by Mattlouf. This strange title, SARKOLONISATION, is a combination of the name of ‘Sarkozy’ and the word ‘Colonization.’ The film is a parallel montage between René Vautier’s film AFRIQUE 50 (1950) and Nicolas Sarkozy’s so-called “Speech of Dakar.” Nicolas Sarkozy held this speech in July 2007 at the University Cheikh Anta Diop in Dakar. A violently racist and neo-colonialist proclamation, it said that “the African is responsible for his own misfortune” and that colonization was a big step forward for the African people.

Two years later, in 2009, SARKOLONISATION appears—which has been made possible because AFRIQUE 50 suddenly became available on the Internet. René Vautier’s denunciation from 1950 offers the perfect answer to each of Sarkozy’s racist allegations—the old colonialist arguments to justify western exploitation.

The most ironical aspect is that the “Speech of Dakar” was itself a sampling of Hegel’s Lectures on the Philosophy of History: “In the main part of Africa, properly speaking, there can not exist any History. What happens is a result of accidents, of surprising facts. There can not exist a purpose, a State that could be a perspective. There is no subjectivity, but only a mass of subjects that are destroying themselves […] The Negro, as already observed, exhibits the natural man in his completely wild and untamed state.” (Hegel 1901: p. 150)2

When René Vautier discovered SARKOLONISATION, he was so pleased he declared it was the best possible use of his film. In 2013, the film cooperative Les Mutins de Pangée published a book and DVD about AFRIQUE 50, and René Vautier wanted SARKOLONISATION to be part of the box set. This can be read as an eloquent gesture from the history of cinema in the direction of everyday digital amateur practices.

But in the context of René Vautier’s work, it was also the result of 70 years of reflection about the powers and duties of the image. Among the actors of history, René Vautier was among those who articulated very precise thoughts on the mission of a film archive: he considered a cinematheque not as a film warehouse but, I quote from a conversation of August 18, 2009, “a place where the memory of the uncontrolled cinema is kept—and a place that helps to keep what was once, temporarily, prohibited.”

Besides spreading the vocabulary of ‘consultation’ (through—for example—captions during exhibitions, precisions in program note), a second task for any film archive may be to reverse the ideological hierarchies, and to consider that the most urgent task is to collect, restore and reproduce a cinema as committed as the one outlined above, which is the most courageous but also at the same time the most threatened cinema in technological terms—because it was mostly shot in 16mm, often without a negative.

As a next step, let us consult an excerpt of the greatest horror film in the history of cinema. It has no real title. In the original, it is just a silent, ten minutes long 16mm reel.

To understand what is at stake, here is a brief chronology of the events that the film is referring to and entangled in:

1928: Jean-Marie Le Pen, far-right politician, is born in La Trinité-sur-Mer. That same year, René Vautier, communist filmmaker, is born in another little port, Camaret-sur-Mer, in the same region, Brittany.

1957–58: during the Algerian war, Jean-Marie Le Pen is a Lieutenant in Algeria and practices torture.

1984: Two French newspapers, Le Canard enchaîné and Libération, publish a dossier recalling the tortures committed by Lieutenant Le Pen in Algeria. This leads to a trial in 1985 because it is prohibited by the amnesty law to spread such information (due to a series of legal decisions, beginning with the decree 62-327, March 22, 1962, granting amnesty for crimes committed under the Algerian insurrection).

1984–88: René Vautier shoots À PROPOS DE L’AUTRE DÉTAIL (About the Other Detail): the ‘Other Detail’ is torture in Algeria, the ‘first detail’ being the 6 million Jews murdered during WW2, something that Le Pen considered “a minor detail” of history. (Le Pen, quoted in Finkielkraut 2006: 103) À PROPOS DE L’AUTRE DÉTAIL is a series of testimonies by Algerian victims tortured by Le Pen himself, to be screened during the trial.

1987: Le Pen declares that he is a candidate for the Presidency of the Republic.

1988: After the trial, René Vautier returns home, to Brittany—and this is what he finds:

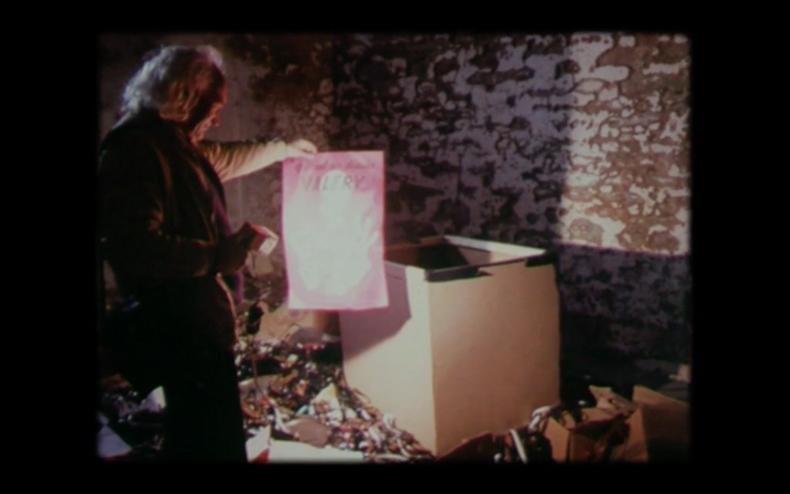

DESTRUCTION DES ARCHIVES (Destruction of the Archives), filmed by Yann Le Masson, shows René Vautier walking through miles of film and non-film documents that were cut with an ax and drowned in fuel oil by an ‘unidentified’ commando. This modest reel is one of the most eloquent symbols of the power of images, a modern photochemical chapter in the long history of vandalism and execration.

From this, we could suggest a third task that is to be fulfilled by a film archive: to put online the fragile and inaccessible committed films, which were never made to have a copyright or to earn money. This is what the Cinemateca Nacional of Venezuela in Caracas once did. It offered the revolutionary film heritage of Central and South America online, films such as EL SALVADOR: EL PUEBLO VENCERA by Diego de la Texera (1980), LA DECISIÓN DE VENCER by Colectivo Cero a la Izquierda, Salvador, (1981) and many other Sandinist and militant films.

Thanks to DESTRUCTION DES ARCHIVES, we can understand more fully the vital importance of SARKOLONISATION for René Vautier: it testifies to the persistence of the political efficiency of images. To show them, to use them, for any means necessary in the present, is to bring them to life.

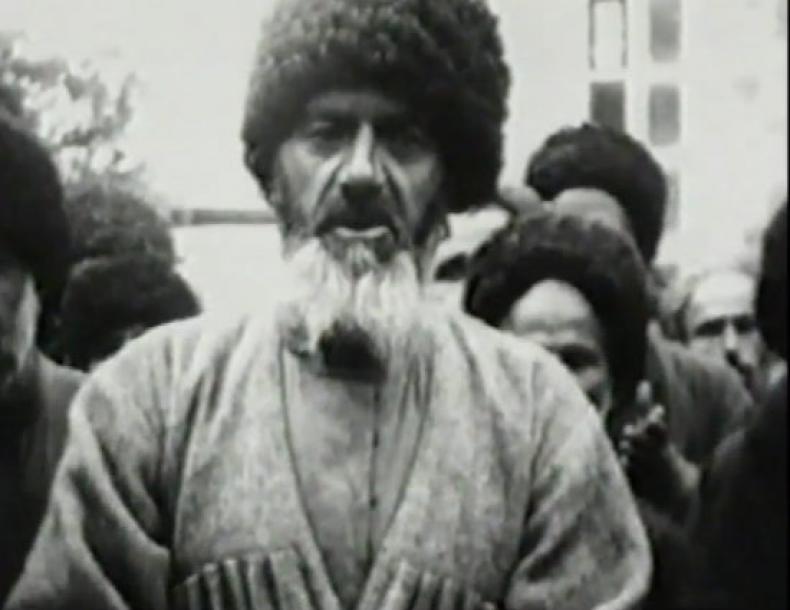

C. This brings us to the third form, the prophylactic use of film: Such a prophylactic use considers film itself as a form of preservation, contrary to the common conception of film as a fragile, instable medium. A fascinating example is ITCHKÉRI KENTI – LES FILS DE L’ITCHKÉRIE by Florent Marcie, 2006. ‘Itchkeri’ is the name that the population of ‘Chechenia’ uses to designate their country, ‘Chechenia’ being the Russian appellation, while ‘Kenti’ means ‘the brave sons of.’ In 1996, Florent Marcie, a philosopher and journalist, made several trips to this so-called ‘Chechenia.’ 10 years later, he edited his rushes into an almost 4-hours fresco about the history and the wars in this country. The following sequence is shot in the central square of Grozny, the capital, destroyed by the Russian army.

Having asked Florent Marcie where the archive footage he used in his film came from, he answered in a private message on November 25, 2014: “I got these pictures from a young Chechen refugee woman in France. They were on an old VHS K7 circulating in Chechnya during the first war. I was never fully certain of their origin, nor do I know the name of the director(s). I can just tell you what was said to me: that these images were shot by the Russian authorities for the usage in propaganda films.”

Despite of the degraded state that these images are in, due to the multiple transferences of the analogue material, they nonetheless work as a symbolic preservation of the Itchkeri people. The similarities of the dances, gestures, costumes, even faces, establish such a strong continuity that the past seems to protect the present: the continuation of a tradition offers a promise of longevity to this people devastated by an on-going genocide. So the original Russian images suddenly turn against their manufacturers and remind us that the longevity of a film reel is estimated to be four hundred years, while a digital document may last only ten years.

SARKOLONISATION, ITCHKÉRI KENTI, and many other examples of course—as Jean-Luc Godard’s HISTOIRE(S) DU CINÉMA (1988–98)—make strong use of degraded films and versions transferred multiple times. They reach a point where ‘degradation’ becomes an unending stylistic resource, as rich and powerful as chromaticism. Like color, since the end of the 1960s, technical transfers became a palette that continuously enrich itself as to technological changes, evolving both by invention and by obsolescence.

2. The Invention of Film as an Aesthetic Model. New Modes of Film Visibility

Thanks to many artists and historians, we know how film, from a simple, raw material, has become the subject of visual investigations, an icon of cinema, a problematic protagonist of the transfer from theatres to galleries and museums, a hero of representation. We must consider that film—thanks to Constructivism, Surrealism, Lettrism, Structuralism—has been one of the most celebrated materials in the history, comparable to marble in the history of architecture. For many digital artists, the textures and light offered by film remain a visual ideal.

But there are also unexpected and discrete new artistic uses of film—of the film as model. I would now like to evoke two cases from the artists Marylène Negro and Jacques Perconte.

In 2010, Marylène Negro agreed to contribute a film for an exhibition entitled ‘Anonymous.’ Her creation, entitled ‘X+,’ explores the visual and acoustic forms of presence thanks to which the photochemical traces of countless anonymous figures can persist, insist or dissolve—traces of those countless figures whose existence forms the tissue of humanity, and whose mingled gestures, noticed or unnoticed, make up the supposed ‘collective’ substratum of collective history.

On her timeline, Marylène Negro superimposed ten activist films from a body of work that has been, in most cases, relegated to the margins of the official history of images; films which were sometimes themselves collective or anonymized. Among these films are, to name some of the famous ones: THE BUS (d: Haskell Wexler, 1963) which shows participants on their way to the Civil Rights March on Washington, or LOSING JUST THE SAME (d: Saul Landau, 1966), which portrays the daily life of a black teenager from West Oakland on his way to prison, IN THE YEAR OF THE PIG (d: Emile de Antonio, 1968), a fresco of the Vietnam war, and WINTER SOLDIER (d: Winterfilm Collective, 1972), consisting of lectures by Vietnam War veterans whose testimony on the atrocities drove them into illegality, WATTSTAX (d: Mel Stuart, 1973), presenting us a concert to commemorate the Watts riots of 1965, or UNDERGROUND (d: Emile de Antonio / Mary Lampson / Haskell Wexler, 1976) about the politics of the Weathermen who went into radical activism and clandestinity.

From this body of work, Marylène Negro has invented a new form of editing that probes depth as well as scope, verticality as well as horizontality. She superimposed the ten films in their whole linearity, and then sculpted their relations of opacity and transparency, so as to bring forth one or several visual and sound images from her volume of layers. Here, the traditional projection of a film is reinterpreted into a digital, horizontal linearity; but it remains a ruling structure, like the scrolling in the projector. While watching this, one has to consider that each silhouette and human presence is for Marylène Negro a visual event, a visual subject sufficient in itself.

The interweaving of these subjects by superimposition becomes a concrete analysis not of a concrete situation, but of complex movements of history. A form of history that occurs through latencies, resonances, deflagrations, involutions, short circuits, lags and synchronies. In this sense, Marylène Negro’s film imagines and thinks collective history in the fullness of its complexities, providing each silhouette its status as a historical agent.

Whereas Marylène Negro takes film as a model of linearity, Jacques Perconte takes it as a model of instability. And indeed, analogue film is unstable for at least three reasons: 1) inside the frame, where the density of the print can vary; 2) from frame to frame, where each frame questions the stability of the prior frame; and 3) when projected, in the movement of traction. Jacques Perconte takes this as his starting point and tries to infuse the instability of the photochemical reel into the stability of the digital world. Let us consider one of the most obviously artistic Lumière films, shot by Félix Mesguisch in 1900: PANORAMA ON THE BEAULIEU-MONACO RAILWAY, that is a true experiment on the textures and optical properties of black and white film in relation to Jacques Perconte’s AFTER THE FIRE made in 2010.

Jacques Perconte invented an algorithm able to ‘glitch’ the colours from the dust and the rays that we can briefly see at the beginning of the film on the train window. It is a way to monumentalize the most volatile accidents, referring to the ‘imponderable’ by which Henri Langlois summarized the genius of the Lumière Brothers capturing the Zeitgeist.

Thanks to this invention, the digital can develop a new sensitivity to coincidence, randomness, accidents, all the phenomena capable of contradicting its own order. Perconte’s work is a permanent homage to the instability of the photochemical print as it can be infused into the digital technologies. When did the history of the positive effects of mechanical reproduction begin, considering reproduction as a creation and as a blessing for elaborating new ideals—especially when the reproduction is a transference and degradation of properties?

3. The Case of a Luxurious Version: and More Tasks for the film archives

In 1912, the founder of iconology, Salomon Reinach, retraced the history of a turnaround: that of the traditional conception of images. Reinach wonders: which historian was the first to consider that an image was not an illustrative and secondary artefact (the mere consequence of a text or the reflection of a referent), but an independent, active and causal element that could trigger myths and beliefs?3

Reinach attributes the turnaround that reverses the status of the image from a determinate artefact to a determining cause, to the mythologist Alfred Maury and his 1843 work, Essay on the Pious Legends of the Middle Ages (Essai sur les légendes pieuses du Moyen Âge). From this I would like to suggest inventing a historical knot that could be useful to our present, and make a connection between such a speculative reversal, the history of photography and the beginnings of mass-circulation of reproductions on paper. In other words, this period when imprints multiply, become popular, free themselves of their origins and begin to roam the world at random. Maybe in seeing how movies are suddenly spreading all over screens and other spaces in degraded versions, we are witnessing the same kind of event that Alfred Maury was seeing when paintings, frescoes, sculptures suddenly spread in the world to produce new ways of inhabiting, populating, enriching it.

One of the most vivid presences of images in our contemporary, visual, overpopulated world appears when the pictures come from tools, or use, or circuit that do not belong to the common industrial organization. This is what I call ‘technical disobedience (see Brenez/Jacobs 2010). A beautiful case of technical disobedience is the work of French artist Jérôme Schlomoff, who now lives in Amsterdam. He is a photographer and filmmaker, and became a specialist of Stenope Film. The specificity of his practice is that he built a 35mm pinhole camera, so his works are technologically free, visually gorgeous and financially feasible. What we see here is anexcerpt of his portrait of the artist Henri Plaat, an example of metaphorizing film in its capacity of birth.

The film describes the birth of an image, a portrait of Henri Plaat emerging from the developing tray. This developing tray is shown serially, in order to evoke the scrolling of frames on an imaginary film while the whole thing is filmed with Schlomoff’s unique, self-built pinhole camera. Schlomoff’s HENRI PLAAT offers a superb case of portraying film itself—and assigning it a general power of birth. Another historical case of crosscurrent technical disobedience is of course Jean-Luc Godard’s new chapter/summary/Aufhebung of his own vast fresco when, in 2004, he decided to retransfer the results of his multiple transferences of analogue to digital known under the title of HISTOIRE(S) DU CINÉMA onto a 35mm film, titled MOMENTS CHOISIS DES HISTOIRE(S) DU CINÉMAcinema (Selected Moments of Histoire(s) du Cinéma). It was a perfect solution in order to maintain that the photochemical print is the future of digital.

But let us conclude with another case that will synthetize some of the previous examples: IXE, by Lionel Soukaz. Lionel Soukaz shot IXE in 1980, after the censorship and ‘x-ing’ of his earlier film RACE D’EP (1979), despite letters of support from Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze and Roland Barthes. In creating his new film, Lionel would now bring forth and aggregate all possible grounds for censorship: heroin fixes, sodomy, zoophilia, pedophilia, blasphemy. A masterpiece of provocation, that remained invisible for decades. It is also a demonstration about most of the gestures that can be made with film: to record, to scratch, to form a hybrid with video, to multiply, to repeat, and so on.4

The origin of this consultation version is the VHS edition published by Re:Voir in 2002. But IXE belongs to the Expanded Cinema tradition, it was made to be a multi-screen projection. In 1981, Lionel explained his dispositif at the Palace: IXE was there projected on 6 screens, and more broadly, was conceived to be presented differently each time. In explaining the concept, Lionel Soukaz evokes a marvellous image: “IXE is like a cat thrown in the air” that will always fall back on its paws (Soukaz, quoted in: Bernard 1981).

In 2004, with Lionel’s help and artistic approval, the French Film Archives (Archives Françaises du Film) invented a ‘restored’ version of IXE in 35mm. But of course, the result of 16 + 16 is not 35. So, what is the correct version of IXE, the reference print? Of course, there is none, IXE is the open whole of all its possible versions: it includes all the consulted and degraded versions, that pleased Soukaz very much, as well as all the expanded performances, as well as its imaginary, luxurious, institutional version in 35mm.

In a way, IXE is both an example of what cinema is—an infinite range of projections—and an advertisement for film archives, which now have to establish all the historical reference data for each work: not only authors, year, length, gauge, speed, but also all the specificities and rules, including absolute freedom, for projection and exhibition.

- 1A more exhaustive list can be checked here: Laboratories, in: Filmlabs.org, http://www.filmlabs.org/index.php/labs/ (September 13, 2016).

- 2“In diesem Hauptteile von Afrika kann eigentlich keine Geschichte stattfinden. Es sind Zufälligkeiten, Überraschungen, die aufeinander folgen. Es ist kein Zweck, kein Staat da, den man verfolgen könnte, keine Subjektivität, sondern nur eine Reihe von Subjekten, die sich zerstören. […] Der Neger stellt den natürlichen Menschen in seiner ganzen Wildheit und Unabhängigkeit dar [...]“ (Transl. N.B.).

- 3This is in the chapter entitled “From the Influence of Images on the Formation of Myths,” in volume IV of his vast fresco Cults, Myths and Religions, which he had been working on since 1905.

- 4On the Internet, this film is now easily accessible, thanks to Kenneth Goldsmith’s Ubuweb, one of the most innovative curatorial project in relation to the avant-gardes: http://ubu.com/film/soukaz_ixe.html .

Bernard, Jean-Jacques (1981): Cinémania. Interview with Lionel Soukaz, broadcast on Antenne 2.

Brenez, Nicole / Jacobs, Bidhan, eds. (2010): Le cinéma critique. De l’argentique au numérique, voies et formes de l’objection visuelle, Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne.

Hegel, G.W.F (1944): Die Vernunft in der Geschichte. Einleitung in die Philosophie der Weltgeschichte [1822–31], in: Hegel, G.W.F.: Vorlesungen über die Philosophie der Weltgeschichte. Bd. 1, Leipzig: Meiner; shortened version in English: Hegel, G.W.F. (1901): Philosophy of History, trans. J. Sibree, New York: P.F. Collier and Son.

Le Pen, Jean-Marie, quoted in: Finkielkraut, Alain (2006): Croatian Nationalism and European Memory, in: Golsan, Richard J., ed., French Writers and the Politics of Complicity. Crises of Democracy in the 1940s and 1990s, Baltimore: John Hopkins UP.

Reinach, Salomon (1912): Cultes, mythes et religions. Vol. 4, Paris, Ernest Leroux éditeur, 94–108.

Renée, V. (2014): The First 8mm Camera Made in over 30 Years Will Be Released in December, in: No Film School, http://nofilmschool.com/2014/11/first-8mm-camera-made-over-30-years-logmar-super-8-release-december (September 13, 2016).